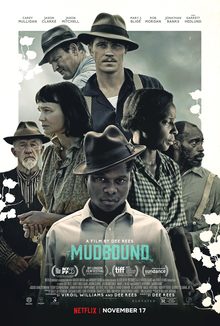

Mudbound

Dee Rees (director), Rachel Morrison (cinematographer), Mako Kamitsuna (editor)

Adapted from the Hillary Jordan novel by Dee Rees and Virgil Williams

Carey Mulligan, Garrett Hedlund, Jason Clarke, Jason Mitchell, Mary J. Blige (cast)

January 21, 2017 (Sundance), September 10, 2017 (TIFF), November 17, 2017 (USA)

Mudbound is a raw, historical family drama with a Faulkernian cadence. The film is a domestic epic that tracks the lives of two intertwined families, one Black and one white, in 1940s Mississippi. Both families have young sons away in the war and both are bowed under the daily struggles of farm life. Both returning sons struggle to readjust to civilian life and both matriarchs are hemmed in by the patriarchal denial of their potential. But these are lonely points of connection in a relationship marked by exploitation and abuse. Mudbound denies no character their humanity or their due—you will know all of its everyday monsters by the time it’s done—but it absolutely condemns white supremacy in all its forms.

Where the white McAllans are newcomers to the farm pursuing a dream of landed Southern gentility, the Jacksons have been working that very same farm for generations hoping to someday buy it. Henry McAllan (Jason Clarke) has long faulted his father Pappy for selling their own inherited land. Although Henry has a successful career in the city as an engineer, he associates land ownership with power. Seemingly on a whim, he tells his wife Laura (Carey Mulligan) that they’ll be moving to their new farm to a pursue a dream of landed Southern gentility. This disrupts the plans of the Jackson family, who have been working to finally purchase the farm for themselves. Hap Jackson (Rob Morgan) is both head of the family and head of the community—when he’s not working sun up to sun down and beyond on the farm he will never own, he preaches at the local Black church. Land ownership is his dream too, because it represents the generational wealth Black Americans have long been denied, but it’s a dream that’s tempered; he reflects on how easily even Black families with deeds are cheated out of their land.

This is the basic setup of Mudbound, the thing that sets these families at odds. I won’t call it a collision course because it’s not a case of two equally opposed forces crashing into each other but rather the slow grinding away of one family’s dignity and safety at the expense of another’s. Because the film is so interior—full of monologues, meditative explorations of character and place—we know the characters intimately, their best and worst impulses, the secret fears we could never read from their faces. Director Dee Rees worked with scriptwriter Virgil Williams to adapt the Hillary Jordan novel of the same name, but in doing so they significantly expanded several roles, very much to the film’s benefit. Florence Jackson (Mary J. Blige), is just quietly supportive in the novel. Jordan doesn’t give us a look into her head, even while we hear from her husband Hap and son Ronsel. In the film adaptation, Florence is just as outwardly supportive, and often outwardly nonreactive to the McAllans’ worst acts, but we also get to hear her voice through a key, added-in speech and several internal monologues. Florence is someone holding herself and her family so carefully, but so strongly, trying to avoid even worse from the McAllans and the other white residents of the town.

The expansion of Florence’s role provides a necessary counterpoint to Mulligan’s Laura McAllan, who, in another film, might have drifted through the film as a gentle wisp of educated, white womanhood. To be sure, Laura got a bad deal in the form of husband Henry, who is a cold lover and a domineering husband. He makes a series of foolish mistakes which moves the family from a comfortable, middle class, suburban lifestyle to an isolated shack on a muddy farm, at odds with their own workers. Laura is miserable on the farm, having gone to teacher’s college and expecting to perhaps work part time even after marriage. On the farm, her every second is consumed by cleaning, cooking, running after her children, and even patching holes in their roof—that is, until Henry decides that Florence will come be Laura’s new nanny and housekeeper. In order for Laura to have time and space of her own, she takes Florence away from her own family, her own children.

Three scenes sum up the relationship between Laura and Florence. Their relationship starts when Henry collects Florence in the middle of the night to attend to his sick children, forcing her to leave behind her own. Florence goes along with it because she knows refusing could have dire consequences. She makes up home remedies for the kids, calms a panicked and hostile Laura, all the while ignoring Henry’s father Pappy hurling racial slurs at her, like some ancient, malevolent spider huddled up in the corner of the room. Once the children are healed, though, and Florence tries to return home to check up on her own kids, Laura tells her that she now has a job. Not asks or offers, simply tells Florence that she’ll be happy to know that Laura is now her employer. Later, when Hap breaks his leg while working on the farm and is laid up in bed for weeks, Laura sneaks into Henry’s savings to send a doctor around for him. Laura cares about Hap, in a way, and certainly feels sympathy for him. She cares about Florence too, distantly, but most importantly she doesn’t want to lose her labour. Florence can’t refuse Laura’s demands or her charity. She knows too well what the price for “not knowing their place,” as one character puts it. It’s a price that Ronsel pays later in the film.

Ronsel Jackson (Jason Mitchell) and Jamie McAllan (Garrett Hedlund) are those two sons lost for a time to war. Their experiences during the war are different—Ronsel a sergeant in a tank crew; Jamie a bomber pilot—but both return changed, traumatized, and unable to connect with their families. They quickly become friends after witnessing each other experiencing PTSD flashbacks and stress reactions, and hide away in an empty barn smoking, drinking, and telling stories. They don’t miss the war but they do miss some things: Ronsel, the relative freedom of being a Black American soldier in Europe, where he was welcomed as a liberator; Jamie, freedom from the toxic expectations of his male family members for whom he, as an actor, was never serious enough, or man enough, for; and both of them, the distance from Mississippi. Their friendship isn’t perfect or equal or entirely healthy—they self-medicate away most of their days—but Jamie does see Ronsel as a brother, and Ronsel slowly comes to trust Jamie.

All of that is shattered by Jamie and Henry’s father, Pappy, in a brutal third act that leaves both families devastated. Pappy McAllan, that spider in the corners of this film, occasionally creeping out to spit poison—that withered old man whose funeral opens the film and whom you keep hoping will kick off now, no now, ok now—does not approve of this friendship. Pappy does die, eventually, but not before causing irreparable harm to both families, sending both lost sons away again. Jonathan Banks, who plays Pappy, infuses a palpable violence in the character from the start, one that slowly builds charge over the course of the film until it finds it’s best moment to strike. I’ve already trotted out “in an another film” once to sing Mudbound‘s praises, but—in another film Pappy may have been played as white, male violence neutered by age, unable to do anything worse than issue threats, as though racial slurs and threats aren’t themselves devastating and violent. Instead Mudbound eases us into seeing the full scope of Pappy’s power, just what he can accomplish with a few young ears, and just what he has raised in Henry and Jamie.

One of the film’s most chilling confrontations starts as a comfortable conversation between father and sons, with Pappy asking Jamie just how many Germans he killed during the war. When Jamie is unable to answer that question—because he was a bomber pilot and there is no way he could know; because he was a bomber pilot and the sheer scope of the death and destruction he caused overwhelms him—Pappy scolds him that a real man should know how many men he’s killed. “How many men have you killed Pappy,” Jamie responds. “Just the one, right?” “But,” Pappy says, “I looked him in the eye.” You know in that moment exactly the measure of Pappy’s character, and exactly what Henry and Jamie have lived with and been accomplice to their whole lives.

It’s difficult to stop talking about Mudbound. It’s not a long film but its structure leaves you feeling like the distance travelled is long. It feels like there is still so much to say. You get to know all of these characters, these people, intimately, and while their story is particular it’s also the story of their town, their state, Mississippi, during and in the immediate aftermath of WWII. Cinematographer Rachel Morrison and editor Mako Kamitsuna make sure that we get to know the land just as well, and understand its character. The film is called Mudbound, after all, and that’s as much about the physical state of being trapped in mud as it is this place and this time and these people: the McAllans rolling in filth of their own making, and the Jacksons slowly and eventually washing some of it off. The film was shot outside and in real sharecropper’s cabins. Even when the land is entirely covered in mud, the sky is wide open and crisply beautiful. The sets and costuming are perfectly period done to the least important details, making Mudbound even more immediate and real. The shoot was only thirty days long so Rees, Morrison, and the rest of the crew had to make the best of the conditions, shooting through storms and even employing someone to drive a water truck all over the set, making mud on dry days. That work paid off because it’s a beautiful film, even considering its often ugly material.