Bloodstrike #1

Rob Liefeld (art and story), Dan Fraga (art), Eric Stephenson (story), Danny Miki (art), Byron Talman (color), Brian Murray (color), Kirt Hathaway (letters)

Image Comics

1993

Bloodstrike’s team leader Cabbot is Cable by another name.

This is not a controversial or vindictive statement; Liefeld’s LEGO-like sense of superheroic character creation (a source of endless fascination for me as well as, I believe, what allows the indie-cartoonist revivals of his Extreme Studios titles in the past five or so years to work so naturally) and his intellectual ownership of Cable proper (having co-created him, in adult form, with Louise Simonson at Marvel) combine to make the re-occurrence of this character in recognisable form a 100% given in his work.

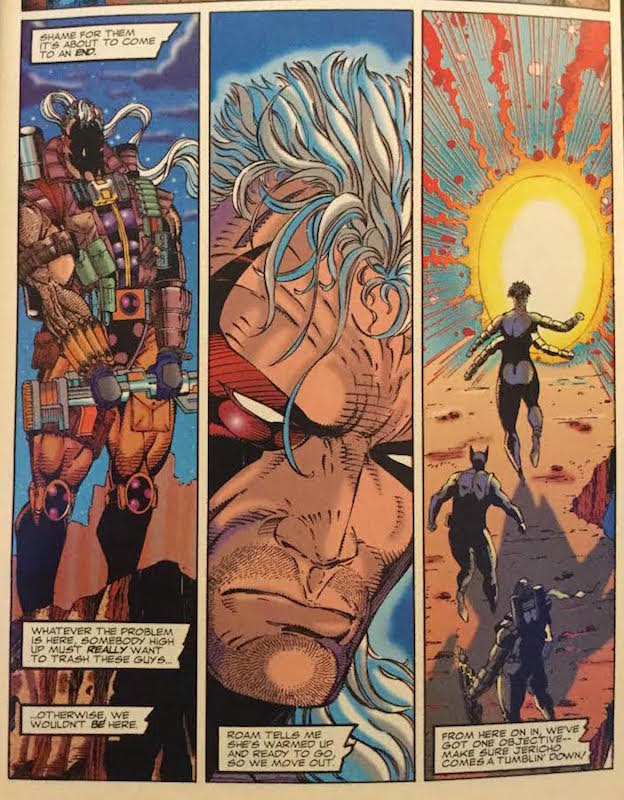

Unlike Cable, Cabbot has a long ponytail, but Cabbot has an otherwise-identical silhouette. Like Cable, Cabbot has a spaceship that can remotely transfer people from place to place and to which he talks (this one called Roam, not Professor), uncommon eye markings, great big guns and a pouch garter. Like Cable and X-Force, Cabbot leads a mercenary team. In Bloodstrike #1 (1993), that team is Bloodstrike.

Bloodstrike #1 is touted in small, missable, but present cover text as the prelude to an event called “Blood Brothers.” Yes, in classic Early Image style, this is a superhero-mercenary team introduced in a book that’s a tie-in to an action-crossover event centred on the emotional ties of that very debuting posse. Overdoing it? Yes. Under baking it? Yes. Sound and fury, signifying significance. Delivering . . . an impressionistic sense of “that time.” I had read this comic more than once before I decided to write about it.

The best thing about Bloodstrike is its colouring. Unlike the Marvel preference for primary colours, under Byron Talman and Brian Murray Bloodstrike favoured the more lurid tertiary ones and plenty of ’em. This lends the book a standout aesthetic and creates a sense of joy that Cable-led strike force teams often lack. The multitude of shades dance with the multitude of bits on Cabbot’s uniform to a Keith Giffen-esque effect, scattershot and uplifting. Every page is a musky rainbow and the Liefeld/Fraga/Miki linework has enough panel and page partitions and swooping above/below angles to give a whirling, almost psychedelic effect. It feels like trying to memorise the exact colours and shapes of a handful of wax dice someone’s tossing up and down, pleasantly stimulating, freed of meaning.

The airbrushed colouring, perhaps unfortunately, was the lone victim of 2017’s Bloodstrike Remastered release (unlike Youngblood’s full script redux). Thomas Mason’s capable re-colour sticks with the basic palette of the original, but (when he’s not reddening browns) mutes, shines, and removes that precious sense of place in time. The Image founders’ styles were so influential that artwork from the ’90s (especially when with their own involvement—Liefeld was on layout breakdowns) can look comic book-timeless; the same can’t be said of colouring techniques and printed pages.

Bloodstrike #1 is not an especially good comic in its own right: it’s not well-written, it’s not easy to follow. It features apparently non-telepathic characters professing knowledge of facts only revealed in other characters’ internal monologue, and the drawings are not always entirely admirable. Cabbot’s outfit may have too many bulky appendages. The female character with four arms is called “Fourplay,” and she’s wearing an X-Men training uniform. Nobody expresses much sense of character, although there are some indications of personal field alliances within the team. There are various nitpicks of taste to be made, but the definite worst element is Stephenson’s script, which features the incomplete or inaccurately assembled sentences and misspelled words that are hallmarks of his early work. That said, his choice to make Shogun—a huge, faceless, metal, gun-filled, flying robo-being—speak like Scott Summers (i.e., “Looks like you’ve run across a bit of trouble, huh, Cabbot? Need a hand?” and “Hold tight people, we’re about to lift off!”) is fairly engaging.

Returning to the negative, the other female member of the team appears to be mute until the twenty-second page of this thirty-two page issue. She speaks once more, on page twenty-three, and neither line provides any character or vitality. As a silent character, she had a certain je ne sais quoi, a Snake Eyes-y seriousness, and Cabbot’s assertion in narrative captions on page eight that she “says she’s anxious to get moving” seemed to express a bond of understanding between them that goes beyond spoken language. That, by implication, establishes backstory and emotional content. As a character who just isn’t given much to say, and whose lines are swallowed up by Cabbot’s internal monologue, she’s a vessel for creator sexism and the implication to the reader that women’s voices don’t matter; that women, even highly trained mercenary women on cool-guy kill-teams, can be spoken for.

Cabbot may be Cable, to a greater or lesser degree. But knockoffiest of all? It’s just not chill to have your Wolverine call someone darlin’.

During this inaugural issue, Cabbot leads his team on a raid. This raid is at a facility of some sort, belonging to a syndicate of some sort, and is revealed in the end to have been ordered by the leader of the security team Bloodstrike finds themselves fighting in an effort to prove himself unfireable. If, he supposed, he could repel an attack by Bloodstrike, he would always have a job defending the compound. Cabbot takes offence at this and, though he technically completes the mission by killing the same security chief who hired him, he ends the issue thinking about how being a mercenary is a dismaying matter of accepting constant betrayal (even though he clearly doesn’t, at least emotionally, accept it). He bemoans being “used,” referring to his job. His job is “mercenary.” Frankly that’s testing the limits of my sympathy.

Liefeld’s panel layouts are alternately great and iffy. There’s a fabulous splash charge that channels the best of John Romita Jr. and Frank Miller’s ’80s woodcut- or frieze-style fight scenes. But there are also some less stylised action panel punch-transitions with perplexing energy transfer. Most of the pages flow well, with the exception of the Image-beloved “turn the book sideways to look at a portrait-format splash page, so you look like a perv reading porno on the bus” that appears just under halfway through.

To end at the beginning, the book opens with a panel that takes up most of the first page and shows our perspective character, Cabbot, grimacing with his face in full shadow. (When I say “full,” I mean “his teeth can be seen shining in non-specific rage.”) This is not an especially great introduction to somebody we’re asked to sympathise with. Sympathy, in fact, is sought to the point that the issue ends on an ominous note regarding Cabbot’s animosity towards his own brother. That tells us that we should care for the humanity in Cabbot; his troubled family life is supposed to matter to us. Remembering the “prelude to Blood Brothers” catch copy, this is a vital aspect of the book! We don’t really see enough of it to believe, but, as with most of what’s found on the page in Bloodstrike #1, sum impression of intention—of character, or grandeur, of extravagance—is enough to make Michel Fiffe’s June-bound foray into the Extreme Studios Revival pool exciting as heck. Who are these people and what do they do? Bloodstrike: Brutalists is coming to tell us, and twenty-five years after this team first hit the page, I’m ready to know.