Brian K. Vaughan (writer), Cliff Chiang (artist), Matt Wilson (colorist), Jared K. Fletcher (letterer/designer), Dee Cunniffe (color flatter)

Image Comics

2015-Ongoing

Paper Girls is an enthralling take on the coming-of-age genre, placing women at the forefront of a number of landscapes they rarely get to star in: ’80s nostalgia pieces, time-travel adventures, horror, and adolescent maturation that focuses on moral complexity rather than the changing body.

The first issue opens with a lonely image of our main perspective character: Erin, dejectedly on her knees, an iconic apple in her hands. The scene quickly goes from remorseful to hellish as a demonic creature tortures her sister and then chastises her for eating from the tree of knowledge.

There’s no doubt that this short episode, with its rapidly changing scenery and juxtaposition of normal school-related anxiety with deep-seated horror fears, is a nightmare. But soon Erin will face a reality just as strange and shifting. After meeting up with three other twelve-year-old paper girls on the morning following Halloween, Erin and her friends are thrust into a strange world occupied by pink sky-rifts, giant pterodactyls, disappearing townspeople, and space-clad newcomers who speak a weird pidgin of Shakespearean English and textspeak. Before long, we see an echo of that first nonsense dream: the apple of the tree of knowledge, this time as the logo for a Macintosh device from some time post-2016.

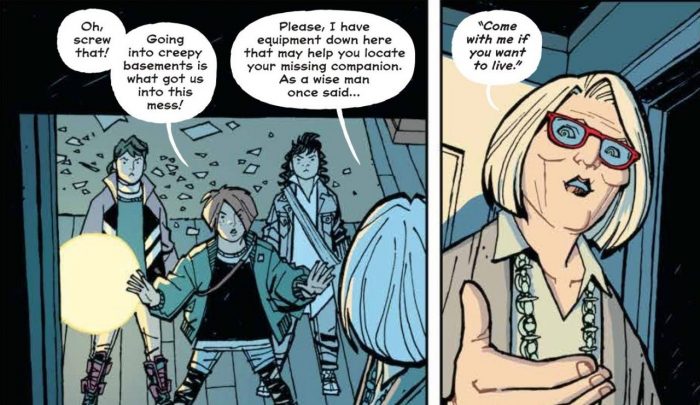

Young and largely powerless within the broader context, Erin, KJ, Mac, and Tiffany survive mostly by stumbling into the right hands or out of the wrong ones. A lonely, anxiety-ridden, Catholic-raised Asian-American, Erin consistently seeks out authority figures to inform or direct her decisions. Even though her circumstances have drastically changed, Erin is still a kid, and still pretty ready to trust anyone who seems like they might know more than she does and doesn’t present an immediate threat. The narrative forces her to recognize that her inherently trusting nature may turn into a liability—but she doesn’t yet fully trust herself, either.

The other paper girls are similarly unequipped to face the epic journey they’ve stumbled into. Mac puts on a tough exterior, but her homophobia and devil-may-care outlook are an increasingly transparent defense mechanism against a life influenced by alcoholism, repression, and bad advice. Unlike Erin, she actively chooses loneliness, because it’s better than being hurt. Meanwhile, Tiffany has rallied her adoptive parents’ high expectations into a confident, almost unassailable attitude, and KJ faces her would-be bat mitzvah and the discovery of her sexuality.

Vaughn doesn’t try to make his characters represent their whole race, class, or orientation, but allows them to grapple with their upbringing and still-forming identities at the same time as they are forced into operation as a team. The ultimately minimal importance of their differences in their ability to be friends seems like a microcosm of hope in the face of the severe imperialist threat of the Future. Although one begins to feel that imperialism must be a constant of history, resistance also seems to be a constant, and so does does the ability to connect despite linguistic, cultural, and personal barriers.

Perhaps this is what’s most alluring about the girls’ journey: not the mystery of the circumstances, but the underlying implications about how meaning is defined by culture–and how culture is not merely geographical, but temporal. 2016-era characters, with their high dependence on computer technology and disappearing malls, are as foreign to our 1988 foursome as are characters from the reader’s future.

The language of the Oldtimers, who seem to be some kind of time travel police, is mesmerizingly both understandable and very foreign, believably evolved from our current slang, and yet untraceably so. What could have made these future humans shift from “my deepest apologies” to “mea maxima”? English seems to have shifted backwards to reaccept more Latin, French, and Old English influence, while also starting to elide more difficult noises like the “th” in “the,” which moves to “de.”

But it’s also picked up a lot of media-influenced words, even in what appears to be official speech, with the Oldtimers using terms like “endcredits,” “poz,” and “forewarding,” even in reports to superiors. Unlike most other futuristic sci-fi with evolved English that I’ve seen, it seems to take a purposeful step away from implying that the power between any two nations has changed dramatically enough to influence the local language away from its roots, and instead focuses on how current slang and formal language might transform over time.

While I would have liked to have seen the influence of Spanish or another largely prevalent American language group on the time-travelers’ speech (more on that in a bit), Vaughn does manage to keep his readers from dwelling too hard on the politics of the future by using influences they are more likely to see as familiar-ish to “standard” English. Textspeak and early modern English are readable to most English speakers, but not usually so thoroughly combined. This keeps our focus on the temporal culture shock, and slightly away from geographically influenced people-group culture shock.

Big name sci-fi (I’m thinking Star Wars, Star Trek, Doctor Who, and even Vaughn’s own juggernaut series Saga) tends to pontificate on the struggle between geographically separated cultures, usually focusing on a presumed East-versus-West, city folk-versus-farm folk, or civilization-versus-“savagery” dynamic, and almost always set in a war or on the brink of causing one. It’s not necessarily a bad way to discuss culture clash and imperialism, as geographically-based culture is what separates most people groups from each other in our relevant existence. But location is not the only thing that creates culture or allows for oppression. One of the major consequences of Judeo-Christian patriarchal imperialism can be seen in the persistent complaints of a certain subset of fantasy consumers that the inclusion of female, queer, or non-white individuals in medieval settings is “unrealistic.”

Setting aside the perfectly reasonable argument that if dragons don’t ruin your suspension of disbelief, women shouldn’t either, the belief that Western Europe didn’t have a plethora of influential women, queer people, and people of color is simply ignorant. But it’s an ignorance born of imperialism, and strengthened by time. We believe it because we’ve been told it’s true. We believe it because there’s no good way for a layperson to easily reproduce the scientific method for history. We can compare one text to another text, but even the texts we are given are curated or created by whoever decided what historical narratives deserved preservation. By creating temporal imperialism, Paper Girls gets the chance to discuss the influence of time and language on our understanding of ourselves in a uniquely explicit way. Who could seize more cultural influence than the person who can literally rewrite history?

I suspect that may be the reason for my main complaint about the series thus far. The only major nod toward non-white influence on language is the shift from “th” to “d”—an easy shift to make, as many modern English speakers already use it in their subvernaculars. I would have liked to have seen some indication that America’s secondary languages (Spanish, Chinese, Russian, etc.) had some larger influence on the primary language of the future, and I don’t feel it would have been difficult to imply without bringing undue attention to other kinds of culture clash. We get the chance to see the girls boggle at the 2016 future and a native 2016-er recall her 1988 reality with almost equal shock. We also get to see prehistoric locals and natives of the far unknown future navigate cultural misunderstandings with our 1988 heroines. If these relatively mundane conflicts can appear and resolve without distracting from the underlying threat of imperial rewriting, it seems like a bit of Spanish influence on FutureEnglish ought to have been well within Vaughn’s abilities, and it’s only because the rest of the narrative holds up both the notes of imperialism and diversity so well that I find this oversight disappointing.

It is unclear whether our imperialists, the Oldtimers, think they are looking out for the girls or intending to hurt them. The politics of the future are muzzy at best, yet the gang is constantly in danger because of them. Secondary characters frequently gain importance and roundness, only to fall victim to the Oldtimers’ utilitarian outlook. We are relatively confident that our paper girls are (mostly) safe, but only because they have somehow accidentally become important to a mysterious Oldtimer who seems to be pulling the strings. If they had not had a chance encounter with some rogue time-travelers that post-Halloween morning, they, too, would be subject to the whims of history, or at least the whims of those who shape it. A self-contained plot keeps Paper Girls from feeling didactic, but the underlying message is clear: the big guys don’t–probably can’t–help the little guys, even if their intentions are good.

While I think Vaughn deserves a little flak for what seems to me a clear oversight in the way American English is likely to evolve in the next couple hundred years, I’m ready to withhold my judgement and wait to see if he gives us any hints at the cause of the linguistic evolution he’s provided. Otherwise, Paper Girls is a refreshingly independent, empowering, and engaging take on the coming-of-age tale. Cliff Chiang and Matt Wilson’s artistic collaboration is striking, complex, and expressive, and Vaughn’s characters feel real: plucky as a team, but flawed and sometimes foolish. In volume three, the plot slows down a little and pulls away from some of the questions of the first two volumes to pose new ones. It remains to be seen whether the story will leave those questions unanswered or circle satisfyingly back, but for now, Vaughn’s bought himself a lot of my faith to wait it out and invest in Erin, KJ, Mac, and Tiffany’s personal growth while the larger plot spirals more slowly on.