So, you’re a mediocre guy who got hit by a truck, stabbed multiple times, or maybe just had a bookshelf fall on you. Unless your name is Yuusuke Urameshi, the story of your near-immediate death is probably not that exciting. Have no fear, the author has decided to throw you into Middle Earth instead! Now you get to be a nerd, but with dragons! Problem solved.

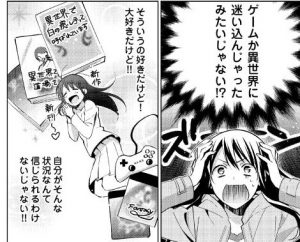

Isekai (異世界, “different world”) is the latest trend to spring out of the Japanese manga market in the last several years, starting with a boom during the late 2000s/early 2010s in the light novel market. While portal fantasies have been a recurring trope over the last few decades (El-Hazard, Fushigi Yuugi, and Red River being a few notable examples), manga adaptations of isekai light novels have become ubiquitous enough that “isekai” turns up page after page of manga on Rakuten (Japan’s equivalent of Amazon) and even isekai manga themselves have begun self-referencing the trope. Popular examples you may have heard of include Is This a Zombie?, Re: Zero, Starting Life In Another World, and KonoSuba: God’s Blessings on this Wonderful World!

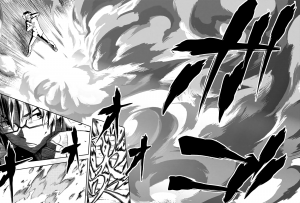

So, what distinguishes isekai from your run of the mill portal fantasy, aside from publication date? Most portal fantasies have the main character pulled to the other world by some abnormal means (like, say, a portal), often creating a moral dilemma of “stay there or go home” that’s hard to resolve. Isekai often will avoid this problem by killing the main character and reincarnating them into a new (usually younger) body. The worldbuilding of the separate world tends to be inspired by RPG worldbuilding (itself inspired by Western/pseudo-medieval fantasy), to the point that actual RPG mechanics (leveling, job classes, crafting, etc.) are sometimes unironically used. Our average hero may have a job that is actually “hero” and have visible pop-up screens to track his hit points and magic points. And usually, the character even if reincarnated will start with some sort of “cheat” to give them an advantage and mark them as special in the isekai—their memories and knowledge from the modern world, absurdly powerful magic, or unique abilities. Isekai’s target audience is the seinen (older boys/men) demographic, which means that other popular seinen tropes (e.g., the infamous harem trope) often get mixed in as well.

![Isekai Kenkokuki chapter 1, art by Koizumi, original manga by Sakura Sakuragi. Published by Young Ace [https://web-ace.jp], 2017.](https://womenwriteaboutcomics.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/isekai2-300x183.png)

But if the stories are that bad, I hear you say, why have they become so popular recently? Because they’re wish fulfillment against a society that is increasingly impossible to fill wishes in. The primary audience for these light novels and manga are Japanese Millennials, facing similar stresses and worries to American Millennials: a difficult job market, open LGBTQ+ struggles, an uptick in mental illness, and the anxieties of an unstable international political sphere. (Sorry about that, Japan. Our bad.) Sometimes it takes all your energy just to get out of bed and not build a guillotine in your backyard, so seeing someone curb-stomp all their problems into submission is cathartic. It’s not a coincidence that most of these characters are in their late twenties, unemployed, and spending their pre-portal time worrying about bills.

If the all-powerful wish-fulfillment appeals to you, there are plenty to choose from: Meikyuu Black Company, Tate no Yuusha no Nariagari, and Isekai to Smartphone no Tomo Ni. But like all genres, not everything falls into the same tropes. Here are a few of my favorites I think have done the isekai trope well.

Honzuki no Gekokujou (本好きの下剋上, Bookworm’s Ascendence)

A rare shoujo/josei example of isekai, the main character is a book lover who dies under an avalanche of her own books, and in a cruel (read: amusing) twist of fate, ends up in a poor family in a medieval-esque world. You know, the kind where books are handwritten and, thus, expensive. Undeterred, she starts trying to figure out how she can make books instead.

In addition to not being a “blow up everything in sight” power trip, I enjoy this one because Main (the main character–no, I didn’t make that up) has no cheats in this world other than her previous memories and knowledge. Being poor and in the body of a sickly five year old, there’s no shortage of hurdles to overcome, which make her small victories all the more enjoyable. I’m always a fan of protagonists who have to think their way through problems. Plus, bookworm? I can relate.

Isekai Kenkokuki (異世界建国記, The Different World’s Nation’s Founding Chronicles)

After dying, the main character discovers his new life is that of an abandoned child, in a forest where lots of parents dump their kids, apparently. Armed with nothing but modern knowledge, he takes a new name, Almus, and organizes the other kids into a self-sufficient community.

The description for this webcomic indicates that this is going to expand into grander, more epic things (the final sentence of the description is のちに『神帝』と呼ばれる男の英雄譚、開幕!!, meaning “The epic of the man who would be called “Emperor” begins!”), but for now, Almus is operating off his wits and memories as a former twenty year old. His “cheat,” per se, is not super magical abilities, but the magical griffin that tasks him with leading the ragtag group of kids, which creates a level of separation and tones down potential griffin ex machina. And hey, I’m a sucker for found families.

Isekai De, “Kuro no Iyashite” tte Yobareteimasu (異世界で『黒の癒し手』って呼ばれています, In A Different World, I’m Called “Black Healer”)

An average female nerd gets literally dragged into a world with RPG stats and quickly, if rather unintentionally, establishes herself as a powerful healer. There’s a lot her magic can’t solve, though, like delivering her the common sense of the new world, putting a roof over her head, or figuring out how to get home.

Aside from having a female lead, this webcomic has a more “standard” plot in the sucked into another world, RPG mechanics sense, but the focus on non-battle/world threatening problems makes this one stick out. The main character, Riin, is also not your typical save-the-world hero: she takes careful steps to avoid getting beholden or tied up in the politics of the country she’s landed in. And there’s no obvious, immediate love interest(s)! (Although some of the guys are pretty easy on the eyes.)

It always interests me to see what kinds of trends are going on in the publishing world, both American and Japanese, and also to see how they contrast against each other. Right around the time that Japan was starting to see its isekai boom (aimed at a Millennial audience), America had hit the rising popularity of dystopia fiction (primarily in YA fiction). Neither of these are a coincidence. Both speak to a young generation that is increasingly and unusually disillusioned with the world they live in. And both speak to the desires of those youth. The Americans, faced with impossible odds, want a small group of determined people to make real change. The Japanese wish to merely quietly disappear.

4.5

I might be mean spirited but once I joked that I want a single chapter Isekai manga where the mediocre guy dies and is reincarnated as an Isekai manga… at which point it loops back at the beginning because he is now this one-shot in our world.

I’d read it!