Hotel Salvation (Mukti Bhawan)

Shubhashish Bhutiani (director), Manas Mittal (editor), David Huwiler, Michael McSweeney (cinematography)

Shubhashish Bhutiani and Asad Hussain (writers)

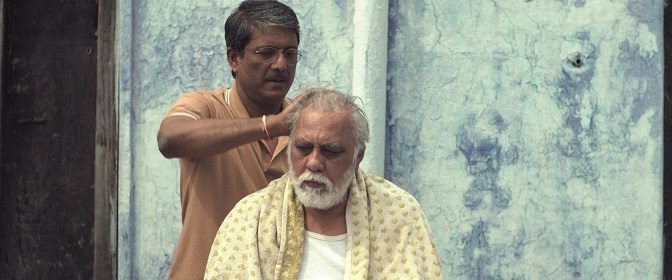

Lalit Behl, Adil Hussain, Palomi Ghosh (cast)

Released April 7, 2017 (India), August 25, 2017 (UK)

Hotel Salvation (Hindi: Mukti Bhawan) is a slow, comic portrayal of grief, death, and letting go. This Indian film by up-and-coming director Shubhashish Bhutiani, tackles big themes in its peaceful imagery and gentle pace and could be part of a new wave of Indian films challenging traditional gender norms.

Hotel Salvation follows a father and son as the father travels to the holy city of Varanasi to die. The film starts with 77-year-old Daya (Lalit Behl) waking from a strange dream with the feeling that he is nearing the end of his life. He decides to travel to Varanasi, where his own father spent his final days. His dutiful adult son Rajiv (Adil Hussain) follows him on his journey. They check into the Hotel Salvation, full of other people waiting for redemption through death.

We wait for Daya’s death alongside Rajiv, who is unused to the gentle pace in Varanasi. Here, people meditate, pray, and sing. They are calm, looking for joy in simpler things. Rajiv, who works a demanding job and is preparing his daughter’s wedding, struggles to assimilate but Daya quickly settles into this new, peaceful world.

The film itself takes on the tone of Daya’s acceptance and the tranquil Varanasi. The camera rests on people and dogs resting on the sun-drenched banks of the Ganges. Wide shots establish the simple rusticity of the Hotel Salvation and its residents. We hang back as scenes are established and players move into frame. The audience feels like observers; we understand that we cannot affect the drama on-screen. There is a sense of mundanity, of daily life, and of inevitability.

In Hinduism, death is seen as both an ending and a rebirth. Hotel Salvation is full of vivid colours even in the homely nature of the hotel. Gorgeous flowers adorn bodies prepared for cremation and ceremonies are full of light, fabric, and dye. This is a film about finding the beauty in austerity, the celebration in pain, the calm in turmoil.

Rajiv struggles to accept his father’s impending death and the audience is unsure, too. Daya feels certain he’ll die soon but his hunch is based on a dream. Amongst the serenity of Varanasi, it’s easy to feel like we’re on holiday, that these men will eventually return home feeling rejuvenated and revived. But Daya insists on staying and spending his last days at the Hotel Salvation.

We are reminded of death throughout the film, as other residents at the hotel pass away. We attend their funerals, hear their obituaries. And despite the bittersweet atmosphere, there is humour. Daya’s nonchalant acceptance of death results in some charming, laugh-out-loud moments. In a memorable scene, Daya enters his new hotel room and we see a cockroach corpse lovingly caressed by the enlightened hotel manager, Mishraji (Anil K. Rastogi). The audience chuckles over this affected performance, yet there is also comfort in seeing respects paid to such a small creature.

Moments like these are what give Hotel Salvation its heart. For a film about grief, it’s a joy to watch. Much of the humour comes from clashes between Rajiv and Daya. As Daya imparts his meditative advice onto his son–relax a bit, spend more time in the present, enjoy the simple things–Rajiv feels like he’s being asked to end his own life, too. They have a strained relationship but nonetheless, Rajiv is scared to lose his father.

In a pivotal scene, Rajiv and Daya face the latter’s seemingly imminent death together. Believing they are in their final moments together, they openly weep, each addressing their broken relationship and the pressure they’ve put on one another over the years. They stroke each other’s faces affectionately and hold one another. It becomes clear how important they are to each other. In this moment, they are stripped of the stoicism expected of South Asian men and they express emotional vulnerability. It’s a rare and beautiful scene, challenging Indian norms of masculinity, and allowing Rajiv to reconsider his priorities and values.

Female gender norms are also subverted by Rajiv’s daughter, Sunita (Palomi Ghosh). At the start of the film, she is preparing for her arranged marriage, like all good South Asian girls do. But she is restless, something her grandfather notices when she comes to visit him. He gifts her his old and unreliable scooter. She promptly goes home, breaks off the engagement, and finds a job.

In a hilarious and frustrating scene, Rajiv video calls Sunita and her mother, Lata (Geetanjali Kulkarni) on a shoddy Internet connection. The sound keeps cutting out and the video barely works, so most of the call involves the characters asking if the other side can hear them. Lata tries to calm Rajiv’s rage and hurt, defensive of her daughter. Nonetheless, the last thing we hear before Rajiv cuts off the call in irritation is Lata saying that Sunita has brought shame upon the family. She is devastated. So is Rajiv.

Sunita’s pursuit of independence is terrifying for her parents but by the end of the film, Rajiv is learning to accept this new way of life for his daughter. Through his own, evolved relationship with his father, he learns to let go of his expectations for his child.

This progression is only possible through the subversion of gender norms. When Rajiv and Daya express their feelings freely, they come to a clearer and more compassionate understanding of one another. In turn, this allows Rajiv to accept Sunita’s assertion of her own freedom, something that is still considered rebellious in much of South Asia.

Sunita’s autonomy echoes a string of recent Indian films that celebrate female empowerment, like Queen (dir. Vikas Bahl, 2014), English Vinglish (dir. Gauri Shinde, 2012), and Angry Indian Goddesses (dir. Pan Nalin, 2015). Even today, desi women are expected to conform to social and gender norms, including standards around marriage, employment, and travel. It’s important for desi women to be able to see female characters in Indian film achieving independence and finding self-worth outside of oppressive social systems.

Importantly, Hotel Salvation does not challenge these norms at the expense of desi culture. Every culture has problems that need to be questioned but western (especially white) society frequently insists the rest of the world reflect their own systems and values, including their flaws and imbalances. In South Asia, modern globalisation and recent British colonialism have resulted in the idolisation and glorification of western ideals and the assumption that white culture is superior. This erases and demeans important desi traditions, cultural touchstones, and positive values.

Instead of inflicting western values onto its characters, Hotel Salvation blends a modern subversion of gender norms with lush imagery of Hindu and Indian tradition, highlighting the film’s bold, Indian roots. Daya attends Hindu ceremonies and practises yoga. He joins in with hymns, even those he’s unfamiliar with. He takes solace in these ancient practices. He is reflective and accepting. He’s also light-hearted; when Sunita comes to visit, they drink marijuana lassi before attending a spiritual ceremony. Sunita’s sober parents can’t understand why the two of them are so giggly and celebratory.

But celebration is the foundation of Hotel Salvation, despite the inherent difficulty of loss and grief. We empathise with Rajiv’s struggle throughout the film but here in Varanasi, death also signifies rebirth. In Hotel Salvation, we don’t just see the end of Daya’s life. We also witness the rebirth of Rajiv and Sunita, who let go of arbitrary duty and expectation, and instead embrace meaning and purpose.