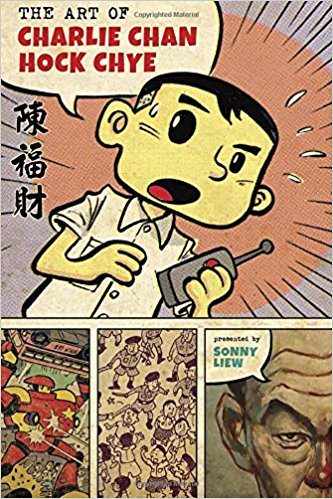

The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye

The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye

Sonny Liew

March 2016

Pantheon Books

The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, has been nominated – and won – awards all over the world. This year, cartoonist Sonny Liew is deservedly nominated for an Eisner for his graphic novel about the history of Singapore through the eyes of a fictional comic artist, Charlie Chan Hock Chye. The book is structured like a biography, combining archival material by “Chye” as well as work by Liew which illustrates their “interviews.” This is so skillfully done that if you didn’t know it was fiction, it would be easy to believe that Chye was a newly discovered, classic Singaporean comic artist. He is a fully realized character, perfectly situated in the Singapore of the 40s and onwards. Liew achieves this partly through the strength of his writing but also because he shows Chye’s style evolving with time and changing to suit whatever he’s working on at the time; Chye’s art is a huge part of how Liew sells the character. The inclusion of real archival material, government morality posters, compared with parodies Chye worked on with a friend’s nephew completes the illusion. Of course all of this shows off Liew’s talent, but The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye doesn’t look like a “Liew book” as you might be used to thinking of of his work. It’s Chye’s book as much as it is Liew’s.

So let’s talk a little bit about Hock Chye, aka Charlie Chan. Despite working on comics from the age of 16 to his death in his 70s, Chye never gets his break. Or any break, really. He continues working on comics because they’re his passion, but he doesn’t even manage to eke out a modest (read borderline poverty as so many comics creators can attest) living from it. Instead he relies on occasional work as a commercial illustrator, night watchman, or whatever else comes by. Chye’s comics are overtly political: social commentary through superheroes like his Roachman, who receives superpowers after being bitten by a cockroach; allegories like his long running Bukit Chapalang strip in which major political figures are recast as cute animal musicians locked in a never ending battle of the bands, not a political one. It’s suggested that part of the reason Chye couldn’t find success despite his obvious talent, is that his comics are too political for Singapore, which had (and to some extent still has) a politically repressive culture. But the other part of the problem is that Singapore is so tiny, unable to support a local comics community because of its small size and the powerhouse comics industries exporting to it, including Japan, Hong Kong, the UK, and the US. Of course, there’s bad luck too – things so often go wrong for those of us working in the arts, no matter how talented you are.

Chye starts out working on radical comics with new friend Bertrand Wong, inspired by contemporary student and union protests. As the fortunes of that real life movement waned, with leaders of Baralis Socialis being imprisoned or exiled and the ruling PAP party inspiring a culture of hollow economic pragmatism, so to do Wong and Chye’s fortunes wane. I mean, it’s not like their comics were selling particularly well, but their hustle was strong enough to have two published comic series under their belts, with 7 and 23 issues respectively. Comics, like any tiny arts community, is a grind though, and after years of it, Wong decides to give it up in favour of starting a real life, with a wife and a real job. Chye, though, isn’t ready to move on from comics – and it’s clear throughout the book that he never will be.

Although Chye’s life is one of frustration, lacking opportunities for personal growth or political expression, comics is what he loves – I guess as much as he does Singapore. Through all the years that he works as a night watchman or whatever else, he keeps at it, making comics daily, perfecting his craft, and commenting on the state of Singapore politics. There’s not a lot of hope for him in the latter, but there’s some comfort in the former. An unfruitful trip to SDCC in the 80s was heartbreaking to read about but even being blown off during portfolio reviews doesn’t kill his love of comics. He returns to Singapore, thinking back on his youth, wondering what he could have done differently. This is explored through a Singaporean take on Phillip K Dick’s Man in the High Castle, where an alternate Singapore where the Baralis Socialis won, and Chye is a considered a national hero, Singapore’s finest and most important cartoonist. He meets his political hero, the prime minister who could have been, who in the real world ended his life in exile, working as a fruit seller. Of course the real world reasserts itself. But Chye’s greatest artistic disappointment still serves to motivate him. It’s “the love of reading [and making] comics… no worrying about how it will sell.”

In the really real world though, Chye is a fiction. He’s a vehicle through which Lieu can explore ideas about what Singapore is, was and could be, and too, his feelings about the comics business. They make interesting companions – Singapore’s economic success contrasted with the narrow Western comics world, a manga scene that continues to be wildly profitable but struggles with digital piracy. But Singapore is more than its sustained economic boom – it’s a country that lost a lot along the way, as Liew points out, and left many behind. Singapore’s rapid economic growth was in part possible because of the policies of its longtime prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, whose political career started in the student and labour movement opposing British colonial rule. Liew takes us through those early revolutionary years from the perspective of someone who is only peripherally involved (Chye). It’s a great way to approach Singaporean political history because as Lee achieves political office and then consolidates power, the country’s politics becomes less and less politics. Though Lee started as a radical, he quickly moved to a more centrist position, eventually becoming an authoritarian capitalist. Until his retirement in 1990 (he was Senior Minister until 2004) he stayed the country’s central and singular political force, rumoured to be willing to do anything to maintain his iron hold on the country’s direction. His is not a wholly dark record though – Liew through Chye concedes that Lee made Singapore a centre of commerce and replaced slums with affordable public housing. But through Chye’s alternate universe story, Liew asks if all the repression, not just of the arts but also the press and all public speech, was worth it. Should Lee’s successor, Goh Chok Tong, who briefly tried to impose eugenicist social policy on the country worth remembering for his successes?

Chye, though, the devoted but fictional Singaporean cartoonist, is worth remembering, despite his failures. While the PAP says that the Singapore Story is one where the “real world triumphs over theory,” Liew shows the party’s real world for the cold fiction it is. In The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, Liew says that dreams, alternative histories and failures are all valuable and worth remembering. His fictional account of one Singaporean, who loves his country and his art, is as real as PAP’s version of history – more even, because in turning his attention to an ordinary life full of good and bad, Liew shares with us a Singapore that’s richer in humanity than the golden island nation PAP has long tried to present. The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye isn’t “the Singapore story” but it’s a Singapore story, a comics story, that’s real and affecting and beautiful.