It’s a good time to be a Wonder Woman fan. Sure, it’s only taken seventy-five years, but the Amazon princess is finally beginning to receive a level of widespread respect equal to the other, mostly male, heroic icons venerated by popular culture. A vast amount of responsibility for this achievement lies with the relaunched Wonder Woman comic, created by author Greg Rucka and artists Nicola Scott and Liam Sharp, which has been given due promotional priority by DC under the high-profile Rebirth banner. The book is, almost without exception, a critical and popular hit.

In fact, the current run has raised eyebrows only once, Late last year, after Rucka’s confirmation that he, Scott, and Sharp were intentionally portraying Diana as queer (not, I should note, for the first time, but perhaps at the point of her highest profile, so that the story was picked up by outlets discussing her film appearance as well). It’s heartening that the greater part of the backlash came not at the idea of Diana being queer, but over whether her queerness can be seen clearly enough on the page. Fans–mostly queer themselves and rightfully keen to be acknowledged and represented in a universe they love–complained that Diana doesn’t label herself outright, nor is she explicitly shown engaging in a sexual or romantic relationship with another woman. This behavior was read as circumspect, near coded, and only visible because of the creators’ confirmation; thus, the argument ran, it doesn’t really count as representation. Without incontrovertible evidence of her queerness, fans feared it could be retconned, excused, or ignored entirely.

Before challenging this view, it’s important to understand why that very valid fear exists among queer audiences. Fan concerns about queer representation in comics and many other forms of popular media are, sadly, often prescient. Fans are wary of tactics designed to attract queer consumers without actually considering their desires: queerbaiting, in which characters are subtextually presented as non-straight, but the creators have no intention of confirming that belief, is seen as a popular way to court a queer audience without alienating a conservative one. The “Bury Your Gays” trope, where explicitly queer characters, especially queer women, receive tragic or fatal storylines at a disproportionate rate, has been nigh ubiquitous on television these past few months, attracting queer viewers only to reject their investment. Creators who discuss their characters’ queerness only outside the narrative, without providing textual support, attempt to appear inclusive but provide no actual reward for fans; the most famous example of this is J. K. Rowling’s post-canonical reveal of Dumbledore’s gayness, which cannot be read in the Harry Potter books themselves. Fans and consumers are right to demand that queer characters be treated with respect and allowed visible presence in their narratives; they are also right to be concerned that even this low bar may not be cleared without vocal demonstration to content producers of its necessity.

It is also important, however, to consider individual cases and not merely wider trends. In particular, Rucka’s previous work inspires confidence. He has a track record of writing, among others, excellent queer women. His argument that Diana has not labeled herself because doing so would be out of character is an expression of the care he takes as a writer. Rucka is never afraid to push boundaries when narrative or character require it. In Gotham Central #10 (October 2003), under Rucka’s pen, Renee Montoya declares, “I’m gay! I’m a dyke, a lesbian, I like girls!” It’s as unambiguous a speech as anyone could wish and the first time, Rucka says, any DC Comics character called herself a lesbian in as many words. Renee’s speech isn’t news to the reader; it marks a shift for Renee from being closeted and forcibly outed to naming and accepting her own sexual identity–it serves the character. Similarly, when Kate Kane says “I’m gay” in Detective Comics #859 (November 2009), it’s not new information; we’ve seen her lesbian identity on the page, and what we learn in the moment is the core of her integrity. As always, Rucka focuses on showing, not telling, the audience what we need to know without shying away from language that suits the character.

The historical importance of coding to queer communities is also a necessary part of this conversation. Fans may be aware of the queer stereotypes that dominated film representation after the Motion Picture Production Code, or Hays Code, of 1930 forbade the acknowledgment of homosexuality on screen and have persisted despite its repeal. Although these stereotypes identified queer characters to straight audiences who often vilified them, they also became signals for queer viewers. More, codes have a long history for many queer groups. The “hanky code” began as a popular method of signaling sexual availability and interest between men cruising for sex in 1970s New York; queer men in England following the turn of the century spoke in slang derived from an entirely different language, Polari. Queer women in interwar Paris wore monocles to identify themselves; around the same time, across the Atlantic, American women sent each other violets as symbols of romantic interest. Again, these and other codes often grew out of necessity, as means of identification in hostile environments where visible queerness could be punished socially or legally, and yet, they still function as community builders. Explicit media representation is always a good thing. But queer coding does not inevitably equal queer baiting; it is a form of recognition and acknowledgement.

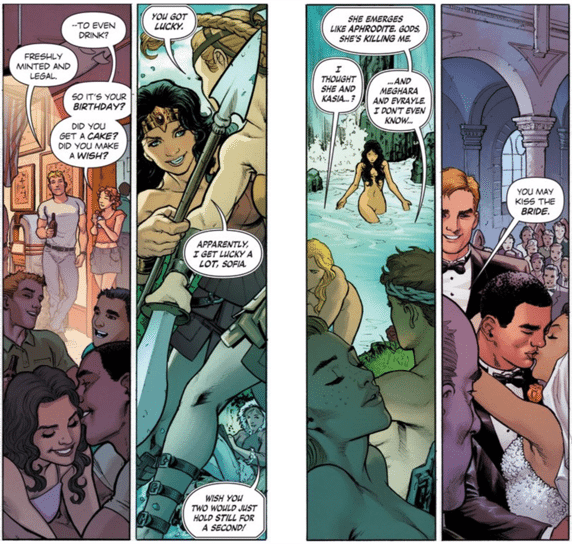

That said, however, Diana is not “merely” coded as queer. Her canonical queerness is partially confirmed through techniques common to comics, which are a visual medium as well as written and use accepted conventions to convey meaning. Wonder Woman #2 (July 2016) introduces us to Diana and Steve through the language of comics. Panels depicting Steve’s life in the Army are interspersed with those showing Diana on Themyscira. We see the two of them at target practice–Diana with bow and arrow and Steve with a gun–and participating in religious rituals (Nick and Maya’s wedding, with Diana and her sisters making offerings to the gods). We also see the different aspects of love present in both their lives: friendly, familial, and, yes, romantic or sexual. Perhaps Kasia’s reference to Diana’s ability to break her heart or the comparison Io draws between Diana and Aphrodite could be read platonically in isolation. In the context provided by Scott’s art, which uses panel structure and visual echoes to emphasise the similarities between Steve and Diana’s lives, claiming Diana’s queerness is opaque while acknowledging that we understand Steve is being flirted with on the same page requires wilful misreading.

Granted, there will always be naysayers and nitpickers keen to insist a fact does not exist unless it can be cited unambiguously. Given that, one could understand the creators taking a moment to revisit the issue. Rather than acknowledging the furor, however, Rucka and Scott continue in Wonder Woman #12 (December 2016) to prioritize character and narrative, presenting an egalitarian view of sexuality while simultaneously demonstrating the function of indirect and coded communication in both heterosexual and queer relationships.

It may seem odd to speak of coding in relation to heterosexuality, and certainly the practice is less widespread. Yet, when Steve and Diana speak of what she left behind, Steve doesn’t ask “Did you have a boyfriend”–having seen Themyscira–or even “Did you have a girlfriend.” He asks Diana if she had “Someone special? Someone…important?” The indirect phrasing tells us a lot about Steve (I was skeptical of Rucka’s pre-series claim he’d make us care about Steve Trevor; no longer!). It too is a type of coded language, but one clear to all audiences when placed in this familiar heterosexual context of a man asking a woman about romance. Rucka uses these phrases with that connotation to once more cast Diana’s relationship with Kasia in an undeniably romantic light, while the wordless panels that follow allow Scott to focus on the connection between Diana and Steve that we know will also develop into a romance. Bi and pansexuality, or indeed any type of non-monosexuality, are often portrayed as though an individual’s identity is determined by the gender of their partner(s); here, however, Diana’s love for Kasia, her love for Steve, and the potential of both are shown simultaneously. The relationships are allowed to co-exist without conflict; neither is labeled “explicitly,” but readers are given the same tools to understand both. Like our initial introduction to Diana’s queerness, these further developments are conveyed organically, in keeping with the growth of the characters.

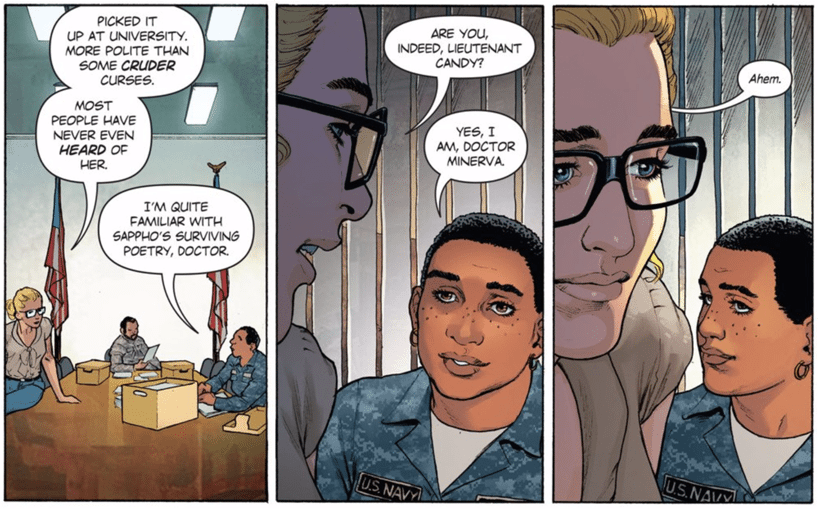

The exchange stands out all the more when compared with one earlier in the issue that demonstrates an admirable grasp of the form and function of coded queer communication. Barbara Ann’s use of “Suffering Sappho!” is a callback to Wonder Woman‘s Golden Age roots. Yet, here it also demonstrates how queer individuals use code to identify and bond within communities. Etta’s familiarity with Sappho of Lesbos, whose life and poetry have been sites of meaning to queer women for generations, says less about her knowledge of Ancient Greece and more about her sexuality, while any doubt that Barbara Ann’s use is wholly academic is erased as Rucka perfectly captures the moment of recognition between the two women. Scott’s panel configuration conveys a sudden intimacy while her art, particularly the women’s facial expressions, emphasizes the shift from conversation to flirtation.

Amusingly, the moment seems to fulfill the same function outside the narrative. Reviews of the issue are split into those that understand the code and those that do not, and I’m surprised not to have seen wider acknowledgment of the fact that Wonder Woman‘s supporting cast–including a woman of color and a woman with a disability–just became even queerer. Personally, I’m thrilled to see queer female friendship, and not just romance, on the page; I look forward to more of the matter-of-fact approach to sexuality and sexual identity the book has thus far adopted. And though I join many other fans in waiting impatiently for Diana to have a female partner with as much narrative import as Steve, I also love having multiple characters whose queerness is not sexualized and yet is accepted as evident within the story.

If anything can be characterized as not explicit enough, perhaps the above revelation about Etta and Barbara Ann qualifies; it does come across as a bit “inside baseball,” accessible largely to those predisposed to get the reference, those who already have the knowledge needed to break the code. Yet, in an ongoing medium such as comics, judging a storyline before we have access to all of it is just asking to be contradicted by future canon; we can’t claim the two of them–or, indeed, Diana–are not queer enough until we see the rest of their stories. More importantly, however, I refuse to believe we must always play to the lowest common denominator in determining representation. Queer content accessible to queer fans is queer content. Queerness cannot be judged only on whether it is clear to a non-queer audience; it must be seen as valid when it uses the language of its community.

I believe Rucka, Scott, Sharp, and Bilquis Evely, the artist who will join the team when Scott departs, will continue to give Diana and her cast storylines that respect the characters as well as the fans who identify with them. Diana’s message of love and acceptance resonates across genders and sexualities; she is an inspiration to many who have always sought to see themselves in her. We are halfway through the first year of the new storyline and the book is actively seeking out and speaking to multiple audiences. I can’t wait to see what else the creators do and how they build on these foundations.

And in the interim, I propose a motion to make “I’m quite familiar with Sappho’s surviving poetry” the queer female equivalent of “I’m a friend of Dorothy.”

Are you? Me too.

(With thanks to Alexander Lyons)

Since this article on WW’s queer impact is so great, can someone do one on the WoC Amazons? Not sure if there were plans for that or if it already happened during the WW Film promo image controversies.