When it comes to the vampire fiction of nineteenth-century Britain, four works in particular are sure to be mentioned during any in-depth discussion. One, of course, is Bram Stoker’s Dracula, published in 1897. Another is Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla, serialised from 1871 to 1872, which continues to inspire writers and filmmakers today. Predating either of them is John Polidori’s “The Vampyre,” a short story from 1819 that defined the archetype of the Byronic bloodsucker; no anthology of classic vampire fiction is complete without it.

When it comes to the vampire fiction of nineteenth-century Britain, four works in particular are sure to be mentioned during any in-depth discussion. One, of course, is Bram Stoker’s Dracula, published in 1897. Another is Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla, serialised from 1871 to 1872, which continues to inspire writers and filmmakers today. Predating either of them is John Polidori’s “The Vampyre,” a short story from 1819 that defined the archetype of the Byronic bloodsucker; no anthology of classic vampire fiction is complete without it.

The remainder of the four is something of a black sheep. It is significant as the first novel-length work of vampire fiction in English, and its name will be immediately familiar to anyone who has performed even the most cursory research into the genre’s beginnings. Yet, it has been only intermittently reprinted, it has never been adapted for stage or screen outside of a low-budget YouTube production, and is today seldom read even by fans of horror.

Its full title is Varney the Vampire, or The Feast of Blood: A Romance of Exciting Interest.

One of the “penny dreadfuls” of the Victorian era, Varney the Vampire was serialised over 109 instalments during the mid-1840s before being published as a novel in 1847. Exactly who wrote it was, for more than a hundred years, a mystery: it was published anonymously, credited simply to “the author of Grace Rivers; or, The Merchant’s Daughter.”

The tangled story of Varney‘s authorship is recounted in Chrsitopher Frayling’s book Vampyres: Lord Byron to Count Dracula. In the earlier half of the twentieth century, the eccentric scholar Montague Summers argued that the series’ author was Thomas Peskett Prest. As Prest had written the most famous penny dreadful of all – The String of Pearls, which introduced the world to Sweeney Todd – he was perhaps a logical suspect for having written Varney, the second most famous penny dreadful. It was only in 1963 that James Malcolm Rymer was established as the author, or at least primary author – a fact that popular fiction historian Louis James demonstrated with the aid of Rymer’s own scrapbooks.

From Ruthven to Varney

As Varney the Vampire predates both Dracula and Carmilla, its main model was Polidori’s “The Vampyre.” A cheap, mass-market series called The Romanticist and Novelist’s Library had reprinted “The Vampyre” in 1840, which may well have alerted Rymer’s publisher Edward Lloyd to the commercial potential of vampire stories.

As Varney the Vampire predates both Dracula and Carmilla, its main model was Polidori’s “The Vampyre.” A cheap, mass-market series called The Romanticist and Novelist’s Library had reprinted “The Vampyre” in 1840, which may well have alerted Rymer’s publisher Edward Lloyd to the commercial potential of vampire stories.

The title character in Polidori’s short story is Lord Ruthven, a coldly aloof yet charismatic nobleman obviously modelled around Polidori’s contemporary, Lord Byron. Amongst those fascinated by this newcomer to London society is a naïve young heir named Aubrey, who ends up on a trip across Europe with Ruthven. While in Greece, Aubrey falls in love with a girl who becomes convinced that Ruthven is a vampire – a claim that is vindicated when her corpse is found with bite marks in its neck. Ruthven is subsequently shot and killed by robbers, but his body returns to life when it comes into contact with moonlight. The story ends with him killing another of Aubrey’s loved ones: “Lord Ruthven had disappeared, and Aubrey’s sister had glutted the thirst of a VAMPYRE!”

In the introduction to his story, Polidori gives an overview of the vampire in legend and poetry. Most striking is his account of the suspected vampire Arnold Paole, an eighteenth-century Serbian whose corpse was impaled with a stake, decapitated and burnt; similar treatment was given to the bodies of Paole’s alleged victims, to prevent them from rising as vampires in turn. Between them, the stories of the fictional Lord Ruthven and the real Arnold Paole provided the essential building-blocks of the vampire genre; the next step was for a novelist to make full use of them.

And so we come to Varney the Vampire, which begins where Polidori left off: with a young woman being menaced by a vampire. “There was the tall, gaunt form,” runs Rymer’s description; “there was the faded ancient apparel—the lustrous metallic-looking eyes— its half-opened mouth, exhibiting the tusk-like teeth!”

The victim is one Flora Bannerworth, and it falls upon her brother Henry – along with secondary protagonists Mr. Marchdale and Charles Holland – to end her nocturnal visitations. They later conclude that the vampire is a local man operating under the name of Sir Francis Varney, but they have a hard time proving this theory.

The pseudonymous Varney turns out to be one of Henry’s ancestors, Sir Runnagate Bannerworth, who had committed suicide a century ago. While the notion that suicides are prone to rising as vampires has a folkloric basis, it tends to be left out of modern vampire fiction – modern culture seeing suicide as a tragedy rather than a sin. Varney, in some respects, is closer to legend than to more recent literature.

Exiting Interest, or Inducing Headaches?

As the lengthy narrative unfolds, it soon becomes clear why this once-popular epic is not as widely read today as Dracula, Carmilla or even “The Vampyre.” Here is a 104-word sentence that is fairly typical of Rymer’s turgid prose:

The astonished, and almost worn-out authorities, hastily, now, after having disposed of their prisoners, collected together what troops they could, and by the time the misguided, or rather the not guided at all populace, had got halfway to Bannerworth Hall, they were being outflanked by some of the dragoons, who, by taking a more direct route, hoped to reach Bannerworth Hall first, and so perhaps, by letting the mob see that it was defended, induce them to give up the idea of its destruction on account of the danger attendant upon the proceeding by far exceeding any of the anticipated delight of the disturbance.

This deep shade of purple would have been forgivable had Rymer actually spun a worthwhile tale, but Varney the Vampire was written with the simple aim of getting an undemanding readership to keep on handing over their pennies. The meandering plot was evidently written on the fly; its frequent lapses into incoherence lend credence to the theory that Rymer was working alongside a co-author or two.

This deep shade of purple would have been forgivable had Rymer actually spun a worthwhile tale, but Varney the Vampire was written with the simple aim of getting an undemanding readership to keep on handing over their pennies. The meandering plot was evidently written on the fly; its frequent lapses into incoherence lend credence to the theory that Rymer was working alongside a co-author or two.

Most obviously, the narrative fails to maintain any consistency in the title character’s backstory. The continuity errors begin when Varney’s real name changes from Runnagate Bannerworth to Marmaduke Bannerworth within the first few chapters. We later learn that Varney is not a supernatural entity at all, but a highwayman who was hanged and then resurrected through galvanism – an idea that was clearly inspired by Giovanni Aldini’s experiments on the body of George Forster, and possibly also influenced by Frankenstein.

This development requires Varney’s initial death, which the story previously established as having happened a century beforehand, to have occurred only a few years previously. To fit the new chronology Marmaduke Bannerworth becomes the father of Henry and Flora, rather than their hundred-year-old ancestor. He also turns out to have been Varney’s old partner in crime, making complete nonsense of the earlier revelation that they were the same person.

The business with galvanism is later dropped, with Varney turning out to have been a genuine vampire all along. The inconsistencies continue: one minute Varney is claiming to have seen the reign of King Edward III in the fourteenth century; the next, his stated age is a mere 180.

The final version of events given in the story is that Varney had lived during the English Civil War, and was sentenced to vampirism by divine judgment for the crime of accidentally killing his son. Louis James, in his book Fiction for the Working Man, argues that this engagement with history reflects a change in public tastes:

These writers [of penny dreadfuls] of course ingurgitated any material to hand, but the historical, with its claims of authenticity which appealed to the cosmopolitan, knowledge-seeking reader, was increasingly ousting the Gothic traditions.

Not that Rymer’s stabs at recreating history are particularly successful, as the exact period of the story is unclear throughout. The early chapters would have to take place around 1740, as Marmaduke Bannerworth’s suicide in 1640 is identified as having occurred a hundred years beforehand, yet Rymer’s introduction to the collected edition locates Varney’s exploits in 1713. In either case the plot thread concerning galvanism would be anachronistic, given that Luigi Galvani was born in 1737. A modern corruption in some of the etexts available online confuses this matter even further by identifying Marmaduke’s suicide as having occurred in both 1540 and 1640.

Not that Rymer’s stabs at recreating history are particularly successful, as the exact period of the story is unclear throughout. The early chapters would have to take place around 1740, as Marmaduke Bannerworth’s suicide in 1640 is identified as having occurred a hundred years beforehand, yet Rymer’s introduction to the collected edition locates Varney’s exploits in 1713. In either case the plot thread concerning galvanism would be anachronistic, given that Luigi Galvani was born in 1737. A modern corruption in some of the etexts available online confuses this matter even further by identifying Marmaduke’s suicide as having occurred in both 1540 and 1640.

During the course of its narrative, the story settles into a family melodrama with Varney downgraded from bloodsucking villain to mere black sheep who can be safely invited to weddings (“I will take Henry with me, and Charles, and Flora, and I’d take old Varney, the Vampyre, too… It would be a good bit of fun to take such a fellow as that to a wedding”). This set-up lasts until Varney leaves the Bannerworths and heads out on his own, encountering various other families in a repetitive and episodic plot. The story eventually reaches the point in which the Bannerworths have become so irrelevant that they can be casually revealed to have died between chapters.

After chapter upon chapter upon chapter of increasingly incoherent adventures, Varney decides to end his wretched half-life; the abruptness of this twist suggests that Rymer was working on orders from his publisher to end the serial. The story had already established that, no matter how badly damaged Varney’s body became, it could always be healed and resurrected by moonlight – an idea lifted from Polidori – and so he is forced to pick an unusual method of suicide. He jumps into the crater of Mount Vesuvius, ensuring not only that his body is destroyed by lava, but also that what little traces remain will never be touched by moonlight.

The Prescience of Varney

Varney the Vampire suffers from many of the same problems that can today be found in the serialised fiction of television and comics. Modern fan terms such as “retcon”, “continuity snarl” and “jump the shark” can be applied to countless moments in Rymer’s story. Nevertheless, in its many clumsy twists and turns, Varney hits upon various ideas that would later be adopted by more competent vampire fiction. Indeed, whole swathes of the genre can be seen in embryonic form within Varney the Vampire.

Varney the Vampire suffers from many of the same problems that can today be found in the serialised fiction of television and comics. Modern fan terms such as “retcon”, “continuity snarl” and “jump the shark” can be applied to countless moments in Rymer’s story. Nevertheless, in its many clumsy twists and turns, Varney hits upon various ideas that would later be adopted by more competent vampire fiction. Indeed, whole swathes of the genre can be seen in embryonic form within Varney the Vampire.

Varney is generally portrayed as a sympathetic vampire who does not really want to harm people but is driven to do so by insatiable hunger. This interpretation became popular in the twentieth century, as did another motif used by Rymer: the close-minded, destructive mob of villagers, an image that Rymer appears to have taken from real-life instances of vampire hysteria.

Rymer plays with the concept of the vampire’s victim becoming undead in turn: “it is dreadful to think there may be a possibility that she… should become one of that dreadful tribe of beings who cling to existence by feeding, in the most dreadful manner, upon the life blood of others—oh, it is too dreadful to contemplate!” Bram Stoker would later build a major plot thread around this idea, when Dracula converts Lucy Westenra into a vampire.

Varney the Vampire also explores the theme of immortality. “[Varney] must be nearly one hundred and fifty years of age now,” muses Charles Bannerworth. “What changes he must have witnessed about him in that time… How he must have seen kingdoms totter and fall, and how many changes of habits, of manners, and of customs must he have become a spectator of.” This concept was largely overlooked by Polidori, Le Fanu and Stoker but emphasised by later writers such as Anne Rice.

The revelation that Varney was resurrected by galvanism foreshadows Richard Matheson’s 1954 novel I Am Legend, a much later attempt to give vampirism a scientific grounding. Rymer uses his plot twist to introduce a humorous episode in which Varney the not-really-a-vampire is chased by bungling, superstitious villagers; here, the story becomes possibly the first vampire parody. Indeed, Rymer is not above including what would now be termed pop culture references: the presence of a minor character named Count Pollidori (sic) is a clear nod to Rymer’s literary model, while the mention of a publication entitled The Bloody Spectre of the Tub of Blood, or the Smashed Gore spoofs the lurid naming conventions of the penny dreadfuls.

All a Joke?

Humorous touches such as these raise a question about Varney the Vampire: was the story all a big joke to Rymer?

In his book Penny Dreadfuls and Other Victorian Horrors, Michael Anglo expresses doubt as to whether Varney was taken seriously by either Rymer or the original readership:

Today, Varney the Vampyre [sic], with its stilted and unlikely dialogue, pedantry, and at times almost biblical style, and its piled-on agonies of horror, is more likely to evoke mirth than terror, but perhaps it was so even in the old days. Perhaps, after all, writer and reader did not take each other seriously. How could they? Yet the old bloodsucker had a very long innings.

Louis James also believed that Rymer was writing with his tongue in his cheek, calling the author “an intelligent and versatile writer, who could manipulate the clichés of Gothic melodrama with a detachment that borders on the camp.”

Louis James also believed that Rymer was writing with his tongue in his cheek, calling the author “an intelligent and versatile writer, who could manipulate the clichés of Gothic melodrama with a detachment that borders on the camp.”

The truth is that Rymer did not take his material at all seriously, but he believed that his readership did. In an 1842 Queen’s Magazine article, the author of Varney demonstrates a deeply condescending attitude towards writing for a popular audience. He states that “If an author wishes to become popular – that is, to be read by the majority – he should, ere he begins to write, study well the animals for whom he is about to cater.” Rymer then expresses contempt for the popularity of macabre fiction:

How then are we to account for the taste which maintained for so long for works of terror and blood? Most easily. It is the privilege of the ignorant and the weak to love superstition. The only strong mental sensation they are capable of is fear… there are millions of minds that have no resource between vapid sentimentality, and the ridiculous spectra of the nursery.

So, there we have it. Varney the Vampire is hackwork in the truest sense of the term, written by an insincere storyteller who felt little but disdain for his readership.

It is scarcely surprising that Varney had a limited shelf-life, and – despite the inventive touches discussed above – made little direct impact upon later works in the genre. While it is generally agreed that Bram Stoker was influenced by Carmilla when he wrote Dracula, there is no hard evidence that he was familiar with Varney the Vampire. As Dracula went on to become the definitive vampire story, poor old Varney was consigned to the dustbin of literary history.

The Legacy of Varney

That said, there are two specific aspects of Varney’s character that linger on in contemporary vampire fiction.

One of these is his name – although, sounding rather comical to modern ears, this turns up mainly in humorous contexts. Scott Massino adopted the title Varney the Vampire for a comic about a Nosferatu-esque bloodsucker with a grudge against Bram Stoker, while Kim Newman’s novel Anno Dracula and Chris Sims’ comic Dracula the Unconquered each borrow Varney’s name for a vampire of lesser status than Count Dracula. An episode of the television series Penny Dreadful mentions Varney as a fictional character, as Abraham Van Helsing and Victor Frankenstein contrast Rymer’s creation with the real monsters that they have personally encountered.

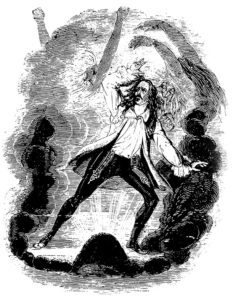

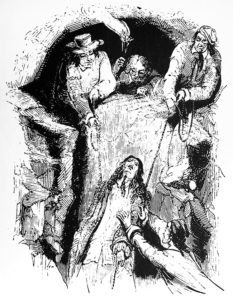

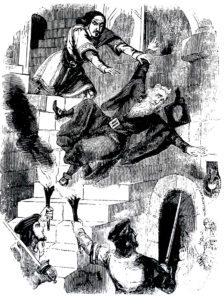

The other legacy of Sir Francis Varney is his image: unlike Dracula, Varney the Vampire contained illustrations. For decades, books on the history of vampires in fiction have reproduced pictures of Varney to show the Victorian idea of a vampire, allowing his image to live on in the popular imagination. It is worth noting that the suave, long-haired versions of Dracula found in Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 film adaptation bear a stronger resemblance to Varney than to Stoker’s description of the Count.

We could, perhaps, venture to suggest a third legacy of Varney the Vampire. James Malcolm Rymer pioneered serialised vampire fiction for a mass audience. In doing so, he prefigured the Dracula sequels of Universal and Hammer; Dark Shadows, Buffy the Vampire Slayer and True Blood; Twilight, Vampire Academy and Anita Blake: Vampire Hunter. Some of these are widely cited as evidence that vampire fiction has gone downhill; but a look at Rymer’s novel will tell you that the genre has always had its weaknesses – not that this ever harmed its popular appeal.

Few people would bother to read Rymer’s story today. But as long as audiences around the world flock to catch the latest exploits of their undead anti-heroes, the spirit of Varney the Vampire will live on.