Following his previous one-shot web manga, Look Back, Shounen Jump+, Shueisha’s online platform, recently published Tatsuki Fujimoto’s Goodbye, Eri.

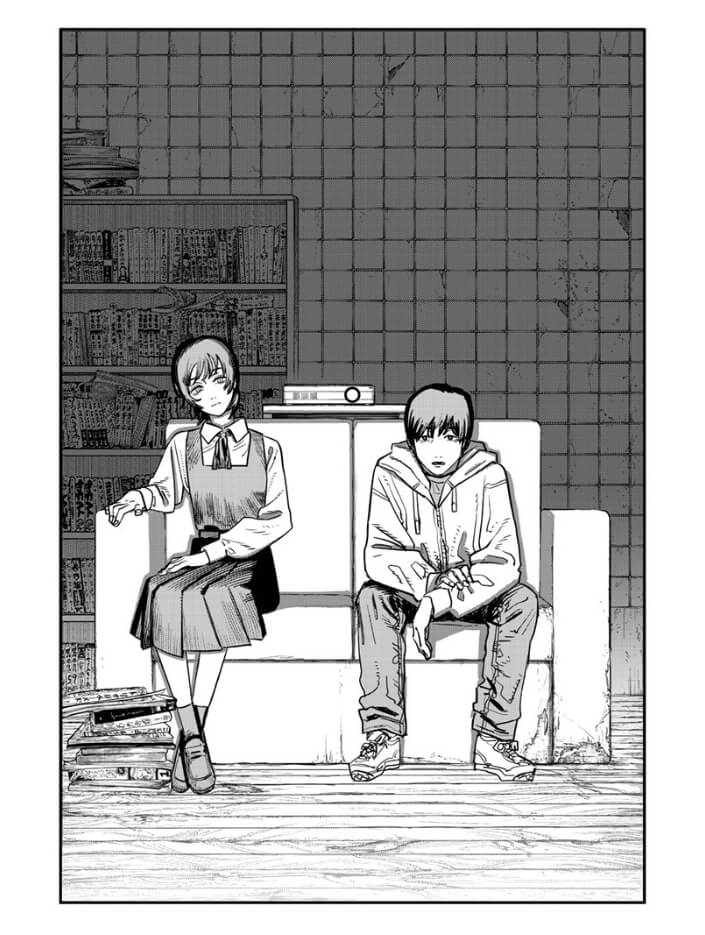

In Goodbye, Eri, a boy named Yuta faces fallout after screening a film about his ailing mother, composed entirely of footage shot of her and his family to the very moments of her death. Yuta becomes jaded by the negative reaction to his film, until meeting a fellow student, a girl named Eri who was actually inspired by it.

Like Look Back, Fujimoto taps into the cycles of pain and grief through the intimate lens of an artist and their creative process, once again using the medium of comics to comment on a medium distinct from it: movies.

Goodbye, Eri

Tatsuki Fujimoto

Published in Shueisha’s Shōnen Jump+

April 2022

Content warning: This work contains depictions of attempted suicide, depression, chronic illness, and hospitalization.

Over time, Yuta and Eri develop a bond fueled by watching movies in the midst of creating one, further unpacking the troubles that were buried deep within Yuta’s relationship with his mother and Eri’s own tragic motives for encouraging this endeavor to begin with. As the film nears its completion with the final question of what its ending should be, Yuta finds himself at the crossroads near the end of his school life, and also unknowingly at what will lead into the end of his time with Eri.

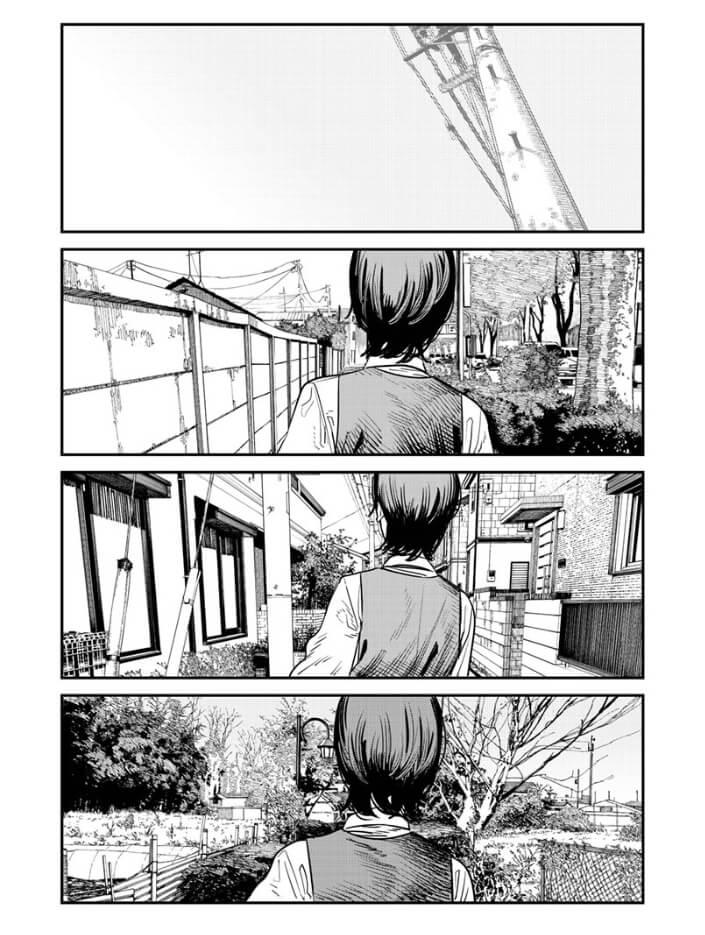

Just as Look Back is a love letter to animators and creators of serials, Goodbye, Eri is a love letter to filmmakers. Fujimoto’s doubles and layers the linework of some panels to create a strobing effect that suggests movement. This effect attempts to convey the motion of video through the limitation of static comic panels. These panels also differentiate from the stylization and framing of the manga’s other panels, which appear sequenced beat by beat as if the frames of an animated sequence were splayed out or a filmstrip has been unfurled. Goodbye, Eri also primarily puts the reader in a first-person point of view in which a character is often directly facing the foreground, presumably in the place of Yuta himself who is holding a camera while trying to record every moment of his life through his eyes. This not only demonstrates Fujimoto’s own mastery of drawing itself, but to the creative use of comic conventions to portray the feel of movies.

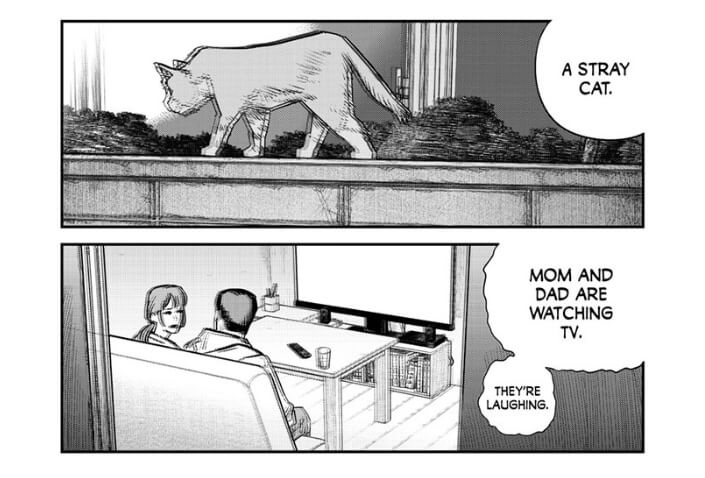

While Fujimoto explores movies on the surface, he is also tapping into the medium’s senses to discuss our personal relationships to memory and memory through the lens—both literally and figuratively—of trauma. It becomes clear that both Yuta and Eri’s penchant for movies and the making of them is some form of escapism. Sometimes things are not always what they seem, and beyond what the camera lens has captured we may not be seeing the whole truth behind an image.

Goodbye, Eri personally reminded me a lot of the methodology within Satoshi Kon’s unfinished manga, Opus, where a manga artist is pulled into his work and is forced to meet with the characters and conflicts he created. Although this is not a unique premise, as the creator confronting their creation is a whole archetype on its own, I found that a lot of Fujimoto’s work strikes a chord very similar to what Kon was exploring himself when it comes to commenting on the medium of art through the lens of societal and interpersonal issues.

Millennium Actress is another Satoshi Kon work that resonates with Goodbye, Eri’s themes, more specifically focusing on the techniques that go behind a production. According to sources in the documentary Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist, Millennium Actress was actually inspired by the intentionally jarring and unconventional editing techniques used in the 1972 film adaptation of Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five. Throughout Slaughterhouse-Five, jump cuts are made to different scenes and characters to create visual parallels and to further disorient the placement of time and space. Millennium Actress does this through animation while Fujimoto has managed to recreate this effect in Goodbye, Eri; while Kon’s film focuses on a protagonist traveling through her memories by re-experiencing scenes like ina documentary, reality also blurs with fiction both on and off the protagonist’s camera versus what he truly experiences in Goodbye, Eri.

Not to box Tatsuki Fujimoto in the shadow of another artist, but the comparison is necessary to note that Fujimoto’s passion for film shows so much in his work just as Kon’s does. Fujimoto has been quoted as being a huge cinephile, often making comments alluding to film in the notes of the chapters of his work published in Weekly Shonen Jump. Through these insights, Goodbye, Eri successfully synthesizes two different mediums to create a unified perspective, just as he has previously demonstrated in Fire Punch and Chainsaw Man.

While Yuta is forced to reckon with his past despite wanting to run away from it by making movies, the titular Eri reconciles with her present through the same process. Although Yuta may have failed in many eyes’ in bidding a proper send-off to his mother, Eri’s motivation to connect with the social outcast is so that he will eventually learn the proper way to say farewell through her. Goodbye, Eri reconciles how art can not only stand in for our pleasures, but that it can service an outlet for our pain as well. But even through all the ways that we may want to use these outlets to forget and run away from the truth behind our grievances, sometimes art’s power and necessity is in reminding us that we have to eventually confront them.