In the previous post in this series, I looked at the short stories and novelettes that were in the running for the 2015 Hugo Awards and may have reached the final ballot had the Sad Puppies and Rabid Puppies campaigns not taken place. Now, for the final post, I shall look at the candidates for Best Novella, Best Related Work and Best Novel.

This article examines the five non-Puppy works that received the highest number of votes in the nomination phase for each category. In the case of Best Novel, that includes three books that made the final ballot.

Best Novella

The Slow Regard of Silent Things, by Patrick Rothfuss

The Slow Regard of Silent Things, by Patrick Rothfuss

Patrick Rothfuss begins this novella by warning the reader not to proceed unless they are already familiar with his earlier books, The Name of the Wind and The Wise Man’s Fear.

Well, that excludes me.

Still, I read The Slow Regard of Silent Things for the purposes of this article. The story follows Auri, a young woman who lives alone in a seemingly abandoned body of underground passages. Her only companion is something called Foxen – possibly a pet firefly, possibly an imaginary friend – although she spends the story awaiting the return of another companion.

As Auri interacts with the inanimate objects that make up her surroundings, Rothfuss draws a persuasive picture of the imaginative life developed by the isolated protagonist. Auri has a number of unusual traits; indeed, her entire personality consists of these quirks. Among them is her habit of anthropomorphising various objects:

Skipping close, she saw a crystal had fallen from the chandelier to lay unbroken on the floor. It was a lucky thing, and brave. She picked it up and put it in the pocket that didn’t have the key inside. They would only fuss if they were put together.

It wasn’t the third door, or the seventh. Auri was already planning her route down to Throroughbottom when she spied the ninth door. It was waiting. Eager.

Speaking as someone who has not read the previous books in the series, I found The Slow Regard of Silent Things to be an intriguing and sometimes haunting story that went on for rather too long. I have no doubt that prior familiarity with Rothfuss’ world would add a new layer of meaning to the story.

“The Regular,” by Ken Liu

“The Regular,” by Ken Liu

Ruth, a detective trying to solve the murder of a sex worker, has a surgical implant that modulates her brain chemicals, thereby allowing her control over her emotions. In the world of “The Regular,” this device is mandatory for police officers as a way of ensuring that they are appropriately impassive while on the beat. Over time, Ruth has begun to rely on the Regulator as a kind of drug – a means of suppressing horror that she has observed in the past. Other concepts that turn up in the story include an advanced motion-detection system, a video camera implanted into the eye of the killer, and cybernetic enhancements that give Ruth superhuman strength.

The problem is that Liu does not explore the full social implications of any of these inventions. Instead, each one is used to accentuate a convention of crime genre: the angst-ridden but outwardly stoic protagonist; the voyeuristic killer; the crucial evidence that does not quite pass muster for legal purposes, necessitating the detective to go a little off the beaten track; the action-packed climax. Indeed, the narrative as a whole hits a lot of familiar genre beats: the protagonist has a tragic backstory involving a murdered family member, which drives her to bypass an impatient superior and confront the killer one-on-one. This is standard territory within detective fiction and cop shows.

Still, while it is not particularly original, “The Regular” benefits from a level of conviction and detail that make it gripping crime story. In particular, Ken Liu pulls no punches in portraying the dangerous lives of those in the sex industry:

The business is competitive, and there’s a brutal efficiency to the [escort] sites that Ruth might have found depressing without the Regulator: you can measure, if you apply statistical software to it, how much a girl depreciates with each passing year, how much value men place on each pound, each inch of deviation from the ideal they’re seeking, how much more a blonde really is worth than a brunette, and how much more a girl who can pass as Japanese can charge than one who cannot.

In a Forever Magazine interview, Liu describes how the story was intended in part to show a world where cybernetic enhancements are considered a banal part of everyday life. This idea does not entirely come through, as the story’s world is too tied to the conventions of genre fiction to convey any sense of everyday life. Still, as an SF-inflected crime runaround, “The Regular” is an entirely solid piece of work.

Yesterday’s Kin, by Nancy Kress

Yesterday’s Kin, by Nancy Kress

Inhabitants of another planet have made contact with Earth, although they are not, strictly speaking, an extra-terrestrial species. They are humans who were separated from our planet tens of thousands of years ago, presumably by some long-gone alien race as an experiment. Since then, their culture has progressed in a different way to that of their terrestrial brethren:

“Most important, the exiles—or at least a large number of them — happened to be unusually mild-natured and cooperative. You might say, ‘sensitive to other’s [sic] suffering.’ We have had wars, but not very many, and not early on. We were able to control the population problem, once we saw it coming, with voluntary measures. And, of course, those sub-groups that worked together best made the earliest scientific advances and flourished most.”

“You replaced evolution of the fittest with evolution of the most cooperative,” Marianne said, and thought: There goes Dawkins.

Shortly after this encounter, Earth is faced with a cloud of toxic spores that threatens all human life on the planet. Will the two strands of humanity join together as a family to see off this danger?

With its themes of prejudice and cultural acceptance, Yesterday’s Kin could reasonably be described as message fiction. But even so, it is message fiction done well. Nancy Kress builds a solid structure around her pleas for tolerance, with almost every aspect of the story tying into the central theme of family.

The main characters are members of a family. One member ends up as something of a black sheep due to disagreeing with the rest on the issues of isolationism and globalisation – issues that the story shows as hinging on the idea of mankind as a global family. Kress makes prominent usage of the concept of the Mitochondrial Eve, a reminder that humanity is one big family. Finally, the revelation that the apparent aliens are actually homo sapiens means that they, too, are our family members.

I cannot describe the story as preachy, mainly because it scarcely has time to preach. The plot, the social commentary, and the usage of science fiction concepts are woven so tightly together that one can scarcely exist without the other two.

“Grand Jeté (The Great Leap),” by Rachel Swirsky

“Grand Jeté (The Great Leap),” by Rachel Swirsky

Mara is a twelve-year-old girl with cancer. She does not have long to live, but she is offered an afterlife of sorts when her father Jakub constructs a lifelike mechanical double for her – ready to receive her brainscan and preserve her mind. The android is named Ruth, after the Biblical character, but Mara struggles to get used to her strange new sister during the last months of her life.

“Grand Jeté” is another story about family. Specifically, it is about a family that consists of a father, a daughter, and two ghosts: one being memory of Mara’s dead mother, the other being the doppelganger-like figure of Ruth. The family is Jewish, existing amidst the twin spectres of the Holocaust and the Israel-Palestine conflict; in addition to facing strain between its individual members, the family has outsider status within its wider community.

In the face of these struggles, Mara’s household still manages to get by. A local store owner, Gerry, is a right-wing Christian, but he remains friendly with the liberal Jewish family despite the differences in politics and religion.

Coping with conflict is a major theme of the story: Mara’s family is, in many ways, is split in two. It is very much living in the past, but it is at the centre of technological progress. Its daughter will die, but in a sense will be reborn. Small wonder that adolescence, itself a transition between two states, is a particularly traumatic process for Mara/Ruth.

From a genre standpoint, Swirsky succeeds in creating an interesting blend of SF and fantasy elements. In the chapter written from Jakub’s point of view, Ruth is described in science fiction terms as a machine containing an artificial intelligence. The final chapter, which follows Ruth’s perspective, captures the explorative aspect of SF with a convincing portrayal of a robot that possesses the memories of a still-living person; it also raises the philosophical question of where Mara ends and Ruth begins. But the first of the three chapters, written from Mara’s point of view, portrays Ruth as a fairy-tale figure comparable to Collodi’s Pinocchio or Hoffman’s Olympia. “Grand Jeté” would make an interesting case study when discussing the boundary between fantasy and science fiction.

It is too bad that the Sad Puppies controversy appears to have cemented, “If You were a Dinosaur, My Love,” as Rachel Swirsky’s signature work. As “Grand Jeté” demonstrates, she is capable of far more sophisticated fantasy fiction.

The Mothers of Voorhisville, by Mary Rickert

The Mothers of Voorhisville, by Mary Rickert

The America of fiction is dotted with small towns in which strange things happen: Arkham, Salem’s Lot, Sunnydale, and now Voorhisville. In Mary Rickert’s story, the town of Voorhisville is suddenly hit by a spate of inexplicable pregnancies, and things get even weirder when the women given birth to babies with tiny wings. Mutants? Devils? Vampires? Angels?

What caused the strange pregnancies is less significant than the effects they have on the populace. The unexplained pregnancies set tongues wagging, and the arrival of the babies leads to the assumption that their mutations were the products of incest.

The story recalls the spate of devil-child narratives that followed in the wake of Rosemary’s Baby. In his book The Monster Show, David J. Skal theorises that this subgenre was partly a cultural response to the thalidomide baby scandal of the late fifties and early sixties. Mary Rickert’s story differs from its predecessors in its nuanced attitude towards the supernatural children.

From the pain and confusion of childbirth to the tenderness and closeness of breastfeeding, Rickert explores the conflicted feelings that any mother will have towards her baby. The infants in the story have the potential to be angels or devils, objects of delight and concern in equal measure. As with so many classics of horror cinema, the most clear-cut monster is not the supernatural character but the torch-wielding mob.

The Mothers of Voorhisville is fuelled by gossip. Rickert uses the strife within the community to tug the reader along through the story, as we are encouraged to listen in on the hushed discussions about sexual wrongdoings. The disastrous effects of such tittle-tattle are then spelt out when a man who has been falsely accused of child molestation seeks his brutal revenge.

Once the story runs out of mysteries to tease us with and begins heading towards its conclusion, it spends a considerable amount of time meandering. The second half of the novella would have been a lot stronger with some judicious trimming. Even so, The Mothers of Voorhisville remains an impressive achievement: it is always good to see a horror story that avoids the clichés and instead aims for a raw emotional impact.

Best Related Work

What Makes This Book So Great, by Jo Walton

What Makes This Book So Great, by Jo Walton

What Makes This Book So Great collects more than two years’ worth of blog posts by novelist Jo Walton. She revisits her personal favourite works of science fiction and fantasy, and touches upon a few of her pet peeves along the way.

The chapters have an average length of three pages each. Although Walton devotes multiple chapters to certain authors – Lois McMaster Bujold gets fifteen, while Steven Brust has seventeen – the coverage of any given novel is inevitably on the brief side. This does not matter too much, as Walton is concerned less with crafting a piece of literary criticism that will endure for the ages and more with expressing her immediate reaction to each work.

It is tempting to imagine Walton with a novel in one hand and a keyboard in the other, as she taps out her ideas as they pop into her head. Just look at this passage from her chapter on Robert Charles Wilson’s The Chronoliths:

Something weird seems to have happened to the Internet, because it’s sort of there and sort of isn’t – there’s something more like satellite TV, and people print things out all the time and have printouts lying around. Maybe that’s what people did in 1999, which is probably when this was written? It feels weird, it feels retro, and I didn’t notice this when I read it in 2002.

It may seem as though this kind of writing could become tedious when carried on for more than 460 pages, but Walton succeeds in keeping her conversational tone fresh and engaging. Her writing is one-third literary analysis, one-third Twitter commentary, and one-third I-found-this-book-you’ll-love-it speech from an enthusiastic friend.

The blog posts are printed in chronological order, but still follow a coherent pattern in terms of subject matter while avoiding repetition – which is more than can be said of John C. Wright’s Transhuman and Subhuman, a blog-derived book that was Puppy-voted into this category. They also appear to have been unedited prior to publication, leading to the occasional oddity such as when Walton asks her readers not to leave spoilers in the comments section.

I suspect that What Makes This Book So Great received a voting boost from people who followed the Tor blog when she originally made these posts. Reading Walton’s commentary in printed form, without the buzzing conversation of a comments section, I have to admit to feeling that something is missing: her analysis is always readable and entertaining, but she tends to skim across the surface of the books she is discussing. No sooner has she raised an interesting point than she moves on to the next three-page chapter.

Still, the next time I need a recommendation for a new SF/F novel to try, I know which book I will turn to.

Chicks Dig Gaming: A Celebration of All Things Gaming by the Women Who Love It, edited by Jennifer Brozek, Robert Smith?, and Lars Pearson

Chicks Dig Gaming: A Celebration of All Things Gaming by the Women Who Love It, edited by Jennifer Brozek, Robert Smith?, and Lars Pearson

From Mad Norwegian Press, the publisher that gave us previous Best Related Work nominees Chicks Dig Time Lords, Queers Dig Time Lords, Chicks Dig Comics, and Chicks Unravel Time, comes Chicks Dig Gaming. A range of authors contribute articles on the subject of games; most focus on either video or role-playing games, although there are a few exceptions – such as Rosemary Jones’ essay on a turn-of-the-century Nellie Bly board game, and Racheline Maltese’s account of how her fondness for chess added stability to her turbulent childhood.

A number of the essays discuss gender issues, but not all are written from specifically feminist perspectives. Topics discussed include gender stereotypes in Professor Layton, the racial identity of Carman Sandiego, the role of imagination in playing a MUD game, and the ghettoization of girl-targeted games. In addition to the more fan-centric contributions are interviews with games designer Lisa Stevens and Dragonlance co-creator Margaret Weis.

Due to its comparatively broad subject matter, the book avoids the repetition found in Queers Dig Time Lords. That said, a lot of the contributions share the overriding theme of “my first time:” fans talk about how they first started gaming, while professionals talk about how they first entered the industry. The purest example of this trend comes from Fiona Moore, who writes an essay on Portal written from the point of view of someone with no prior interest in video games.

I found Chicks Dig Gaming to be an entirely enjoyable book, but as with Queers Dig Time Lords, I am left with the question of whether this kind of fan-blog material is really suited to a major SF award.

As a side note, co-editor Jennifer Brozek was a Best Professional Editor (Short Form) choice in both Puppy slates, on the back of her anthology Shattered Shields. She was nominated, but the Worldcon voters placed her behind No Award. This would suggest that the No Award voters were motivated largely by opposition towards bloc-voting, rather than – as I have often heard suggested – against the political views of the individual nominees.

Invisible: Personal Essays on Representation in SF/F, edited by Jim C. Hines

Invisible: Personal Essays on Representation in SF/F, edited by Jim C. Hines

Jim C. Hines has gathered together a collection of essays in which contributors discuss minority representation in fantasy and science fiction. The familiar axes of race, gender and sexual orientation are covered, along with less talked-about groups: particularly eye-opening for me was Nalini Haynes’ essay on how albinism is almost exclusively used in popular fiction as a visual shorthand for untrustworthiness and evil.

Each contributor belongs to the group covered in their essay, and is able to contrast fictional portrayals with personal experience (“if people didn’t really ‘see’ color, why was I the only one getting asked about martial arts and told that I speak English very well?” writes Michi Trota).

Invisible is a very short book, with a print length of just 54 pages, and the essays themselves tend towards brevity. Most of them are written at the level of immediate emotional reaction, with the case studies being chosen on the basis of what the authors were exposed to while growing up. This is an entirely legitimate approach – after all, the title does identify the contents as personal essays – but there is room for more comprehensive overviews, ones that take wider-ranging looks at fiction past and present. Had the book contained a few more scholarly essays, then it would have been a stronger contender for the award.

I can heartily recommend Invisible, but it really is a bite-sized sampler. There is more, much more, that deserves to be written on each of the subjects discussed by the contributors.

Shadows Beneath: The Writing Excuses Anthology, by Brandon Sanderson, Mary Robinette Kowal, Dan Wells, and Howard Tayler

Shadows Beneath: The Writing Excuses Anthology, by Brandon Sanderson, Mary Robinette Kowal, Dan Wells, and Howard Tayler

Amongst other things, the Writing Excuses podcast features brainstorming sessions in which the crew come up with ideas for stories. In Shadows Beneath, we see the fruits of their labours…

Mary Robinette Kowal’s “A Fire in the Heavens” follows a group of travellers from a culture that reveres the Pleiades, as they end up in a foreign land of moon-worshippers. Much of the conflict derives from cultural differences: one major plot point hinges on a mistranslation. It is reminiscent of Arlan Andrews’ “Flow,” one of the Sad Puppy picks for Best Novella, which has a similar plot – although Kowal renders his two fantasy cultures in richer detail.

Dan Wells’ “I.E.Demon,” the shortest entry in the anthology, is a humorous story about soldiers in Afghanistan using a captive gremlin as a power source. The tale is enjoyably light-hearted – perhaps too much so, given its thematic backdrop.

Howard Tayler’s “An Honest Death” involves a pharmaceutical corporation that has found a way to prolong human life by a century, or even more; it consequently receives a threatening visit from Death, who is most displeased by this development. The premise sounds like a Far Side cartoon, but Tayler aims to make the idea as solidly grounded as possible. He develops the traditional image of the Grim Reaper into a convincing alien entity: using thermal imagery, the protagonists learn that Death’s cloak and scythe are actually a wing-like membrane and a single, bladed arm. The narrative itself is set against a solidly-constructed backdrop of industrial espionage, written from the wry perspective of an everyman security guard.

The last of the four stories is Brandon Sanderson’s “Sixth of the Dusk.” This tale takes place on an island, the inhabitants of which are granted seemingly supernatural abilities by a local species of bird; the protagonist, a trapper named Dusk, is able to see visions of his possible demise. While hunting he encounters a woman from the mainland – a technologically advanced society that has been visited by spacefaring colonists. The story’s Avatar-like conception of magical islanders falling under the sway of imperialistic space-travellers could have been trite, but Sanderson succeeds in portraying the poignant sight of a unique culture that is about to be changed forever by an outside force.

The second half of the book offers an insight into the making of each story, with transcripts of brainstorming sessions followed by early drafts and additional commentary. Any writer of fantasy fiction should find plenty of food for thought here.

Despite its many virtues, I will have to acknowledge that Shadows Beneath seems to be something of a grey area in terms of eligibility. Anthologies of short stories are generally ineligible for the Hugos; a book of this type qualifies for Best Related Work only if it contains a substantial nonfiction component. In Shadows Beneath, that component consists largely of transcripts from three seasons of Writing Excuses – two of which had already been nominated for Best Related Work.

Tropes vs Women in Video Games: “Women as Background Decoration,” by Feminist Frequency

Tropes vs Women in Video Games: “Women as Background Decoration,” by Feminist Frequency

And here we come to Anita Sarkeesian, a person who could do a better job of dividing opinion only were she formed from sapient Marmite.

In this two-part video, Sarkeesian and her co-writer Jonathan McIntosh chart the history of sexualised women being used as eye candy in video games. This trend began in the early days of video arcades, when advertising fliers showed scantily-clad models posing next to game cabinets, and continued through to the sexy trackside girls of the racing genre.

The video then goes on to analyse how games such as Grand Theft Auto have used sex workers and strippers as side characters, with the player encouraged to interact with them for sexual services. Sarkeesian demonstrates how some games actually reward the player for attacking or killing these women; she argues that when male characters are treated in similar ways, the results lack the element of sexualisation.

In the second part Sarkeesian takes a closer look at sexualised depictions of female death, along with games in which women are abused by villains (or in some cases anti-heroes controlled by the player) to provide a gameplay mechanic. She argues that such portrayals offer a skewed and reductive impression of sexual abuse, and cites Papo & Yo as an example of a game with a more productive representation of domestic violence.

At one point Sarkeesian discusses studies that demonstrate the effects of gender stereotypes in the media – but does not actually identify the studies or the people responsible. This lack of citations is one of the main points of criticism directed at her work. It should be remembered that not all of Sarkeesian’s detractors are anti-feminist: certain sex-positive feminists have questioned her attitudes, and her repeated usage of the term “prostituted women” in this video did not endear her to the sex worker lobby.

As somebody who has not played any of the games examined in the video, I am not in a position to discuss the rights and wrongs of how Sarkeesian represented them. My general impression is that while the video has shortcomings, these are largely excusable when we consider its format.

Almost by definition, a video lecture will consist of choice clips and cursory comments; a lack of nuance is to a significant degree unavoidable. Viewing it as an attempt to start discussion, rather than a be-all-and-end-all statement, I would say that “Women as Background Decoration” does its job: Sarkeesian and McIntosh have taken a common but under-analysed element of popular media and given it a wide-ranging and thoughtful overview.

That said, once again I have to question this work’s eligibility for a Hugo. Does it really constitute a “related work” in the context of fantasy and science fiction? Most of Sarkeesian’s talking points are games themed around the crime, sports, war and Western genres. A few of them are fantasy, granted, and at the very end she talks specifically about sexual violence in fantasy worlds, but the issue she is discussing transcends genre.

Best Novel

The Three-Body Problem by Cixin Liu (Hugo winner)

Written by Chinese author Cixin Liu, The Three-Body Problem begins with a prologue set during the Cultural Revolution. Scientific theories deemed reactionary by Communist authorities – such as general relativity or the Big Bang – are suppressed, even if it involves their proponents being murdered by the Red Guard.

The story then skips forwards a few decades. It arrives at a society that appears to have lost faith in the future, the utopian promises of Communism having ended in disaster. And then, Earth receives a radio broadcast from an alien civilisation…

The aliens themselves do not appear in the novel until towards the end; it is the mere potential offered by extraterrestrial contact that is significant. Humanity reacts in different ways; some people view the aliens as gods to be worshipped, while others view them as an agent of revolution: a force that will save the Earth by wiping out humanity.

The above synopsis is very much a simplification of a complex narrative. Liu incorporates a dense body of thoughts into his story, his characters discussing topics that range from astrophysics and quantum theory to the rise and fall of civilisation. Liu uses an impressive range of storytelling techniques to get his ideas across.

An early part of the novel, in which protagonist Wang sees phantom numbers appear before his eyes – counting down to a point in the future of uncertain significance – has a genuinely eerie quality to it, like a ghost story. A concurrent plot thread involving the mysterious deaths of scientists, meanwhile, is the stuff of thrillers.

Another way in which Liu articulates his ideas is through symbolism, as in the scenes where Wang enters a virtual reality game called Three Body. Here, the protagonist encounters digital versions of real-life scientific pioneers such as Newton, Galileo, and Einstein.

The ensuing discussion of intellectual history is dreamlike and surreal – and yet, solidly grounded in science. Once chapter sees the virtual Newton transform an army into a living computer, with ones and zeros replaced by soldiers holding up white or black flags; an amusing image, and one that carries an additional layer of irony when we consider that the entire scene is taking place inside a computer.

The novel’s cover carries a quotation from Kim Stanley Robinson, hailing The Three-Body Problem as “The best kind of science fiction, familiar but strange all at the same time.” I am inclined to agree: Liu uses models that will be readily identifiable to Western SF readers, but he does so in a way that is fresh and inviting. While most of the novels that I read for this series have merit, The Three-Body Problem stands out as the one most likely to be remembered by future generations as a classic of SF.

In terms of Puppies-versus-non-Puppies, The Three-Body Problem is something of a grey area. It was not on either the Sad or Rabid slates, but received a last-minute endorsement from Vox Day, making it a kind of honorary Rabid Puppy book. However, the Puppy opponents who placed slated works below “No Award” were willing to give Liu’s novel a pass, and the book’s acceptance by all sides of the debate no doubt helped propel it to the top.

Ancillary Sword, by Ann Leckie (Hugo nominee)

The sequel to Ancillary Justice, Ann Leckie’s 2014 Hugo-winner, Ancillary Sword continues the exploits of Breq – an artificial intelligence that once operated a spaceship but now inhabits a human body. Breq is coming to terms with her history as a pawn of the imperialistic Radchaai regime, and has agreed to go on a very personal mission: to protect the family of a person she had previously killed.

The first novel in the series introduced a set of SF concepts that would have made rich pickings for any follow-up. How would Breq, once a hive-mind, adjust to existing in a single body? Indeed, the Radchaai emperor is itself a hive-mind: Ancillary Sword takes place during a civil war between two duelling sides of the despot’s personality, making it impossible for a citizen to side with the emperor without simultaneously committing treason against said emperor. There are the makings of a thoughtful meditation upon the nature of personality here.

However, Leckie spends little time exploring the SF concepts that she has dreamt up. Instead, the novel is primarily a family saga – with all the bonding, feuding and occasional loss that implies – which happens to be set against a space opera backdrop. There is definitely something of the kitchen sink drama about the story, with a key scene involving the smashing of a china tea-set.

Breq’s main role in the narrative is that of the observer; she spends much of the story watching the goings-on within the family while contemplating her own contributions to the imperialist regime. The combination of themes – family strife and crumbling empire – sometimes makes the novel feel like an odd, spaceborne version of The Jewel in the Crown. But as the novel lacks either a grounding in real-world history or sophisticated SF worldbuilding, the success of the narrative will depend largely on how the reader engaged with the first book in the series.

The novel was followed by a third book, Ancillary Mercy, and Sword is manifestly the middle volume in a series: one that assumes that the reader was hooked by the first installment and will eagerly pursue the fill-in until the final book arrives.

Because of this, Ancillary Sword strikes me as a redundant nominee. It does not stand as an individual work when read separately from Ancillary Justice, which had already won the previous Hugo for Best Novel.

The Goblin Emperor, by Katherine Addison (Hugo nominee)

The elfin emperor has died, and his eighteen-year-old half-goblin son Maia ascends the imperial throne. Neglected and kept out of the court by his distant father for so long, Maia suddenly finds himself placed front and centre in imperial affairs: all around him are new allies, and new enemies. The intrigue grows thicker still when Maia learns that his father’s death may not have been an accident…

The Goblin Emperor may have a title that smacks of generic fantasy fiction, but its approach is rather more unusual than might be expected. While the novel involves elves and goblins, they are treated essentially as two human ethnic groups. The world includes steam-powered and pneumatic vehicles, but its overall technology level is unimportant; the story barely qualifies as steampunk. Supernatural elements are kept brief and incidental.

Instead of magic or even science fiction, the secondary world of The Goblin Emperor seems constructed from episodes of real-life social evolution, particularly those that occurred in the nineteenth century. The Goblin Emperor depicts a land that is in the throes of change: the new emperor has a keen interest in reforming his empire; a movement for women’s liberation is underway; technological progress is gathering pace faster than ever before; and the working classes are embracing a quasi-Nietzschean doctrine that gods were created by men, and that men can consequently become gods. Addison appears to have placed her tale of courtly intrigue in a fantasy world, rather than a real-world era, as a means of exploring historical themes without being tied to historical fact.

At the centre of all this is the richly-drawn narrative of Maia’s life in the imperial court, a world of luxurious trappings and suffocating formality. The driving conflict is Maia’s quest to uncover hard truths, all the while trapped in a cultural location designed expressly to cover obscure the truth with pomp and circumstance.

On a personal note, I found The Goblin Emperor refreshing in part because it is one of the few novels I have read for this series that is neither a sequel, nor designed expressly to lead into a sequel. If the Hugos are anything to go by, the stand-alone novel might be something of a dying art in SF/F.

City of Stairs, by Robert Jackson Bennett

City of Stairs, by Robert Jackson Bennett

The Continent was once home to a group of divinities. Although believers differed on how to interpret their teachings, the existence of these entities was an objective fact. But they were not immortal, and the colonised nation of Saypur successfully wiped them out in an uprising.

Accompanied by her bodyguard, Sigrud, a woman named Shara Thivani travels to the Continental city of Bulikov to solve a murder; her journey takes her to a magical place where the old gods may not be dead after all…

In one of the earlier posts in this series, I commented that Charles E. Gannon’s Fire with Fire felt like an Ian Fleming novel in space. Well, City of Stairs is another spy/SFF hybrid, but this time it feels like John le Carré adapted to urban fantasy. Robert Jackson Bennett incorporates thick layers of political intrigue into his worldbuilding.

The novel’s world is built upon ambiguity. This can be seen in its political backdrop, with a conquering nation being subjugated in turn. It can also be seen in its portrayal of the Continent’s divinities, which are distinctly two-faced entities. They served as the religious core of society, but at the same time they have an unknowable, Lovecraftian aspect to them.

With all these shades of grey in place, City of Stairs has the perfect backdrop for a story of intrigue and sinister mysteries amidst a sprawling urban landscape. The novel portrays a world in which traumatic history is repressed, existing just below the surface but always threatening to burst out once more. When it does so during the climax, the story reaches hallucinatory heights.

A splendid novel; it is too bad that Kevin J. Anderson’s comparatively unremarkable The Dark Between the Stars was nominated instead.

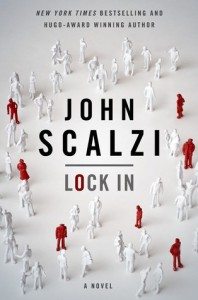

Lock In, by John Scalzi

Lock In, by John Scalzi

In the future, a percentage of the population is beset with Haden’s syndrome, a condition that can leave its victim physically paralysed. Fortunately, modern technology has given a lifeline to those afflicted. By using mentally-controlled robot bodies, colloquially known as “threeps,” Hadens are able to operate in the outside world with a degree of normalcy.

Another new development is the discovery that certain people can have their bodies controlled by the mind of a separate individual, thereby giving Hadens the opportunity to occupy a fully-functioning human body.

Ideally, of course, the owner of the host body approves of how it is being used. However, the process can be put to immoral use – as we see when an unknown criminal takes over someone’s body and uses it to commit murder. It is up to Chris Shane, a Haden detective, to find the culprit.

Until the Puppy campaigns got underway, John Scalzi was something of a Hugo fixture. His work has been nominated for Best Novel four times, with his book Redshirts winning the award in 2013; he has also won in the Best Fan Writer and Best Related Work categories, with additional nominations for Best Novella, Best Short Story and Best Dramatic Presentation, Long Form.

Although he is frequently criticised in Puppy circles, Lock In shows that Scalzi has clear skill as a storyteller: his plotting is taut, his narrative fluid, his prose a joy to read. The charm of Scalzi’s work derives in large part from the convincingly human dialogue of his characters, with genuine personality shining through the high-tech trappings.

The story’s climactic action scene, in which Chris hops between two bodies during a shootout, is a fine example of how the novel works on two levels: a visceral thriller that gets mileage out of an engaging SF conceit.

In building a crime-and-punishment narrative around his science fiction concepts, Scalzi is able to touch upon the ethical issues that often come with new technology. Gun responsibility is an underlying theme in the novel, and is most obvious in a scene involving a Haden militia (the members of which, in reference to Tea Party iconography, dress their threeps as the Founding Fathers). Later on, a sympathetic character shoots dead a home invader – who was, in fact, an innocent man being mind-controlled by the story’s villain. The fact that the shooter is black and the victim Navajo allows Scalzi’s characters to discuss racial tensions.

Given Scalzi’s past exposure at the Hugos, it is perhaps fair that, in 2015, a few other authors had their time in the sun. Still, Lock In is a fine novel, and would not have been out of place on the ballot.

Conclusion

I have now covered every single prose fiction and related work nominee in the 2014 and 2015 Hugo awards, along with a number additional works that I felt were relevant. Here are the conclusions that I reached.

Firstly, I found that a lot of the accusations directed at Hugo-nominated fiction by the Puppy campaigners were unfair.

Sad Puppy founder Larry Correia, obviously with his tongue in his cheek, claimed the Worldcon preferred to nominate “heavy handed message fic about the dangers of fracking and global warming and dying polar bears and robot rape as a bad feminist analogy with a villain who is a thinly veiled Dick Cheney.” But in looking at the 2014 nominees and 2015 longlist, what I actually found was a generally varied and good quality body of work.

Admittedly, some of them are poor (“The Day the World Turned Upside Down”); some have merit, but are flawed as works of fantasy (“The Water That Falls on You from Nowhere”); some are entirely competent pieces in their own right, but not really award-worthy (Queers Dig Time Lords); and some are just flat-out odd (“If You Were a Dinosaur, My Love”).

But sitting alongside these are the solidly-conceived science fiction of Ted Chiang’s “The Truth of Fact, the Truth of Feeling” and Tom Crosshill’s “The Magician and Laplace’s Demon”; the intelligent explorations of race and gender motifs in Kai Ashante Wilson’s “the Devil in America” and Catherynne M. Valente’s Six Gun Snow White; the sheer creative enthusiasm of Writing Excuses; and the precise storytelling of John Scalzi’s Lock In.

On a similar note, the Sad Puppy slate was nowhere near as disastrous a body of work as I had been led to believe by many of the campaign’s detractors. True, Wisdom From My Internet had no place on the ballot, and “Championship B’tok” was a rather curious pick. But in slating the likes of Jim Butcher, Arlan Andrews, Rajnar Vajra and Kary English, the Sad Puppies had at least partly succeeded in their stated aim: obtaining recognition for deserving writers who had been neglected by the Hugos.

As I write this, my general impression that the culture war surrounding the Hugos will end with everyone involved getting bored and going home, nursing their resentment all the way.

I look back over the stories that I covered in this series – the high-flying adventures, the giddy emotional journeys, the gleeful explorations of future technology, the all-round enthusiasm for a possible future – and I cannot help but sigh.

It did not have to be this way.