The Gap of Time: a Novel

The Gap of Time: a Novel

Jeanette Winterson

Hogarth, October 2015

The thing about submerging yourself into Jeanette Winterson’s prose is that you can’t just take the easy road through the story: Winterson demands active participation from her readers. She may cushion you with ethereal sentences and dazzling metaphors, but that doesn’t soften the landing after she pulls the rug of obliviousness out from under your feet.

So, Jeanette Winterson covering Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale? Yes, please. Winterson’s retelling is the inaugural release from the Hogarth Shakespeare series that commemorates the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death (in 1616) with eight contemporary adaptations by a range of authors, from Winterson to Margaret Atwood to Jo Nesbo. In 2016, we’ll be treated to adaptations of The Merchant of Venice, The Taming of the Shrew, and The Tempest. Margaret Atwood is doing that last—and wow. I expect that will be very interesting.

The Winter’s Tale, as retold by Winterson, straddles divides of all kinds: the Atlantic ocean; gender; sexuality; wealth; power. It is brutal and beautiful and—as much as the characters stand out as constructs—it is also very real. Whether or not you’ve read or seen The Winter’s Tale (I have, but it was over a decade ago), you’ll recognize the characters. They are as close to, and as far from, everyday life as are the people featured on the evening news.

As in Shakespeare’s play, Winterson’s tale is divided into two periods of time separated by sixteen years. Although the prose is written in past tense and mostly in third person, the author’s omnipotent view grants the reader access to the inner thoughts of many different characters, which gives the story a kind of immediate proximity. There’s no hiding, here. All is laid bare.

The cast of major characters includes: Leo, a powerful yet morally dubious businessman; Xeno, a video game creator and Leo’s boyhood (boy)friend; MiMi, renowned singer and Leo’s wife; Shep, a widower in America’s deep south; Clo, Shep’s happy-go-lucky son; Pauline, Leo’s morally responsible business partner; Perdita, Leo and MiMi’s mislaid daughter; Zel, Xeno’s estranged son; and Autolycus, a used car wheeler and dealer.

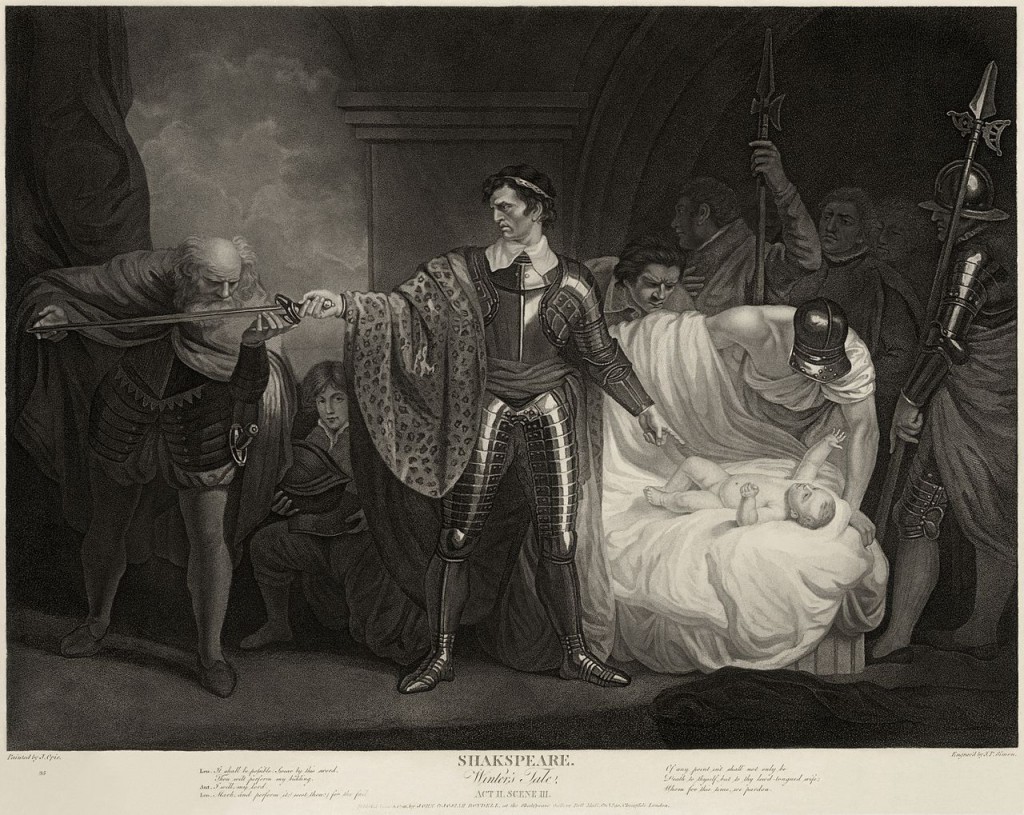

After MiMi gives birth to a daughter, Perdita, Leo continues to insist that she’s not his daughter, in spite of evidence to the contrary. Leo decides to send Perdita to Xeno, but Perdita’s courier dies along the way and she is lost. MiMi vanishes from view—perhaps dead, perhaps simply hidden. Fortunately for Perdita, Shep and Clo find her and raise her as part of their family.

Years later, teenage Perdita falls in love with Zel, who is working for Autolycus. The secrets around her birth come out, and Perdita becomes determined to meet her birth father. She and Zel travel to meet Leo; Xeno, Shep, and Clo follow with Autolycus. The families are reunited and resolved, more or less. A happily ever after ending for Perdita and Zel? Well, maybe. Instead, let’s just say it’s a beginning.

The wealth of the story lies not in the events, but in the whirlwind of angst surrounding them. Winterson’s portrait of Leo, Xeno, and MiMi evokes the emotionally crippled, jaded characters of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. Leo and Xeno, in particular, suffer from privileged disconnection and have little ability to see beyond their own concerns. Their inability to fully resolve a disastrous event from their childhood has painful ripple effects throughout the lives of those around them—and they only begin to recognize that after Perdita and Zel force the issue.

While I would recommend this book based on the lovely prose and depth of character, I also offer a note of caution: Winterson includes a jarring, graphic rape scene—which I’ll discuss below.

To be clear, it’s not like Leo is suddenly an angel by the end of the novel. (Well, he is—in Xeno’s game, but he’s a brutal, vicious fallen angel.) And although it’s clear that he regrets his actions toward his wife and his longtime friend, I wouldn’t say that he’s learned anything. The emotional journey is not his own, but that of his daughter.

This story of forgiveness (not redemption, no, but forgiveness) is woven through multiple layers of reality. Winterson has forged a tale as layered and ephemeral as memory. The first layer is the narrator’s—Winterson, who tells the story through the lens of herself. She even reinforces this through a few contemporary references, including to one of Winterson’s other works, The PowerBook, and to artist Tracey Emin, whom Winterson has called “an avenging angel, swiping at both high art pretensions and mass-culture.”

Winterson deftly maneuvers through all of these layers of reality and more, dropping metaphors here and there like breadcrumbs for the enterprising reader to follow. What makes this book successful, though, is that the breadcrumbs are integrated well enough that they’re not screaming out for attention; instead, they add context and poetic depth. This is a read that bears returning to over the years, across your own gap of time.