Strange Fruit #1

Strange Fruit #1

J.G. Jones and Mark Waid (Authors), J.G. Jones (Artist), Deron Bennett (Letterer)

BOOM! Studios (July 2015)

(This review contains some spoilers)

Writing about Strange Fruit #1 has been a long time coming. It has been on my very-reluctant radar since it was announced on February 20th — Dwayne McDuffie’s birthday. For readers who are unaware, Dwayne McDuffie was one of the most prominent black comics writers and, arguably, one of the most prominent black activists working within the industry. He is one of the few faces that looks like mine whose work specifically aimed to promote other faces like mine in the comics — on the page and off it — and for that alone, he represents a lot.

And his birthday was the day BOOM! Studios elected to announce that two white men would be writing and drawing a title about the racist South called Strange Fruit.

Before I go on, I know, already, that there will be people who would like me to “just stick to the comic” or maybe even “stay in my lane” — despite the fact that this, if anything, is my entire superhighway. After all, I’m promising you a review here, and I’m talking about the announcement of the comic? What gives? You just want to know whether it’s good or not, whether you should buy it, right?

However, that’s a question in two parts: “Is it good?” is a different question from “Should I buy it?” I’m going to answer both throughout this, but my general thesis is this–Strange Fruit #1 could literally have been comics’ Second Coming of the Messiah and I would still think it shouldn’t have been made.

Okay. Now that I’ve got that out of the way and people can either rage quit or tweet about my obvious bias in regards to this comic and their creators – Super looking forward to a white person calling me racist, by the way. First person who sees it, screencap and send pics – I can elaborate a little further on whether the work is good and whether you should buy it.

Now, beyond the fact that the comic was announced on a day honoring who is likely the most prominent black comics creator, it is also mentioned – both in the initial release and the solicit, that this work is a “deeply personal passion project” for creators Mark Waid and J.G. Jones III.

To which I have to say, “Excuse me?”

No, seriously, stop a second and look at this constellation of events. This comic, announced on Dwayne McDuffie’s birthday, about racism in the South by two white men is being marketed as a “deeply personal passion project.” Do I need to go into why I have some questions about why a story about racism is deeply personal to white people? Do I need to explain why I think that marketing choice was tone-deaf and perhaps even toeing the line into disrespect? Do I need to air my concerns about what that indicates about who this book is being marketed to and why I suspect it is not people who look like me?

The next argument might be that I can’t lay this at the feet of the creators because they can’t be responsible for the way their PR team has decided to put their work forward, but this is a pretty weak claim considering creator-owned comics tend to mean that the creators approve how and when their work is shown to the public. It gets even weaker when you know that neither Waid nor Jones is new to this game, or even that Waid had a brief stint as Editor-in-Chief of BOOM! itself. However, the coup de grâce is when you read the quotes from the CBR interview that likely lead to that line in the solicit, which I have excerpted here:

JONES: So why do this story? Why not do something easier and more comfortable? Because this is a passion project for me. It’s a chance to use fiction to take a look at some hard truths — things that I have been chewing on since I was a youngster, and that we have not finished working through yet in this country.

WAID: …That kind of world-building is an incomparable experience, and the opportunity on top of that to write a character piece with the power of history behind it, folding in the stories that my grandparents and my great-grandparents told me about the South back in the day, to hear and weigh those voices again as an adult — that’s what makes this one so personal.

I haven’t even got to the actual content of the comic but these two quotes are exemplary of what I am going to be saying about it and why I felt the way I did before I even started reading. The reason why this comic was, amongst other things, A Bad Idea is because two white men are writing and drawing this book about racism and they have already decided that it is about them.

So, with all that in mind, let us talk about the comic proper — starting with the title.

For those who don’t know, “Strange Fruit” is the title of a song protesting American racism and, particularly, the lynching of blacks, and was made famous by black singer Billie Holiday in 1939. The lyrics to the song are haunting and speak of this strange fruit — that is, black bodies — that swing in the southern breeze. And they are the kind of lyrics that are, as a decades-long symbol of both protest and mourning, dare I say, deeply personal.

Some will be eager to point out that the lyrics of “Strange Fruit” were originally written by a white Jewish man, Abel Meeropol. I will be equally eager to contend not just that Jewish people, at the least, have their own personal history with slavery, but also that the first time “Strange Fruit” was actually recorded as a song, Meeropol made sure to have a black singer, Laura Duncan, perform it. This choice has significance which I will touch on later, along with the contemporary use of white words for black pain.

With the knowledge of this song’s significance to Black Americans, we are once again in territory that is tone-deaf at best, disrespectful at worst, and, to say the least audacious because honestly, how dare you? I am genuinely taken aback at the presumptuousness it takes to, as a white man, decide that it’s probably cool for you to name your comic after a song that has meant so much to a people who have suffered and are suffering under your legacy and power, a song that viscerally depicts this physical suffering. I mean, no wonder white men like writing superheroes so much — obviously the feeling that they can do anything they want makes perfect sense to them.

Now, let us open the comic.

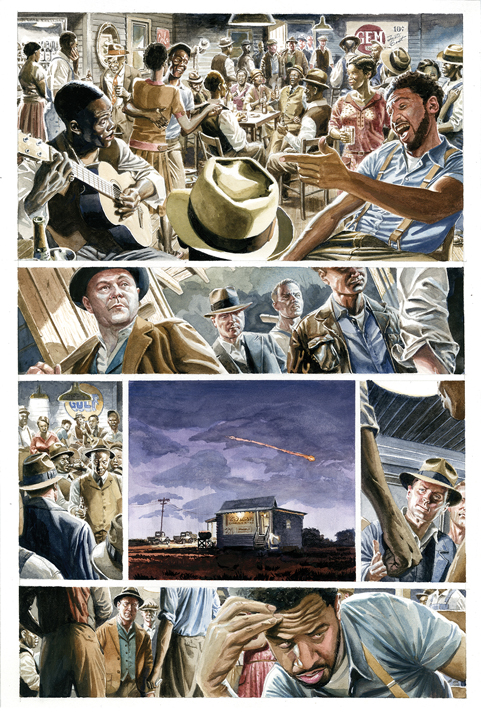

The art is gorgeous and most panels are the kind of thing you could easily imagine framed all their own. The choice to paint is an interesting one and, for me at least, evokes Norman Rockwell’s well-known illustrations Saturday Evening Post. That’s a kind of jarring association, when Rockwell’s focus was on idyllic American life while the material Jones is depicting is anything but.

I also think that the word bubbles and lettering do not mesh at all with Jones’ painted art. The margins surrounding the text are a bit too large and started to give off a sort of scanlation kind of feel — like the real text is in another language and I’m seeing a dub, so to speak. The flatness of the bubble would integrate just fine with a comic done in a more traditional style, but it’s really not working against paintings. It looks like they’ve been slapped on top and don’t quite belong. What’s more, the lettering itself is also a bit too close to Comic Sans than I’m fully comfortable with.

Still, the panel layouts are visually stimulating and there is quite a lot to like in this regard. I always enjoy art that breaks into the panel gutters to convey active movement, though this is a semi-common technique, and we have the usual use of one action bridging several panels of different focus to create the sense of motion — an old trick that I also confess satisfies me every time. However, Jones also adds some interesting round inset panels, which you don’t see very often, and has one page in particular that I thought was stunning, though it still needs some unpacking.

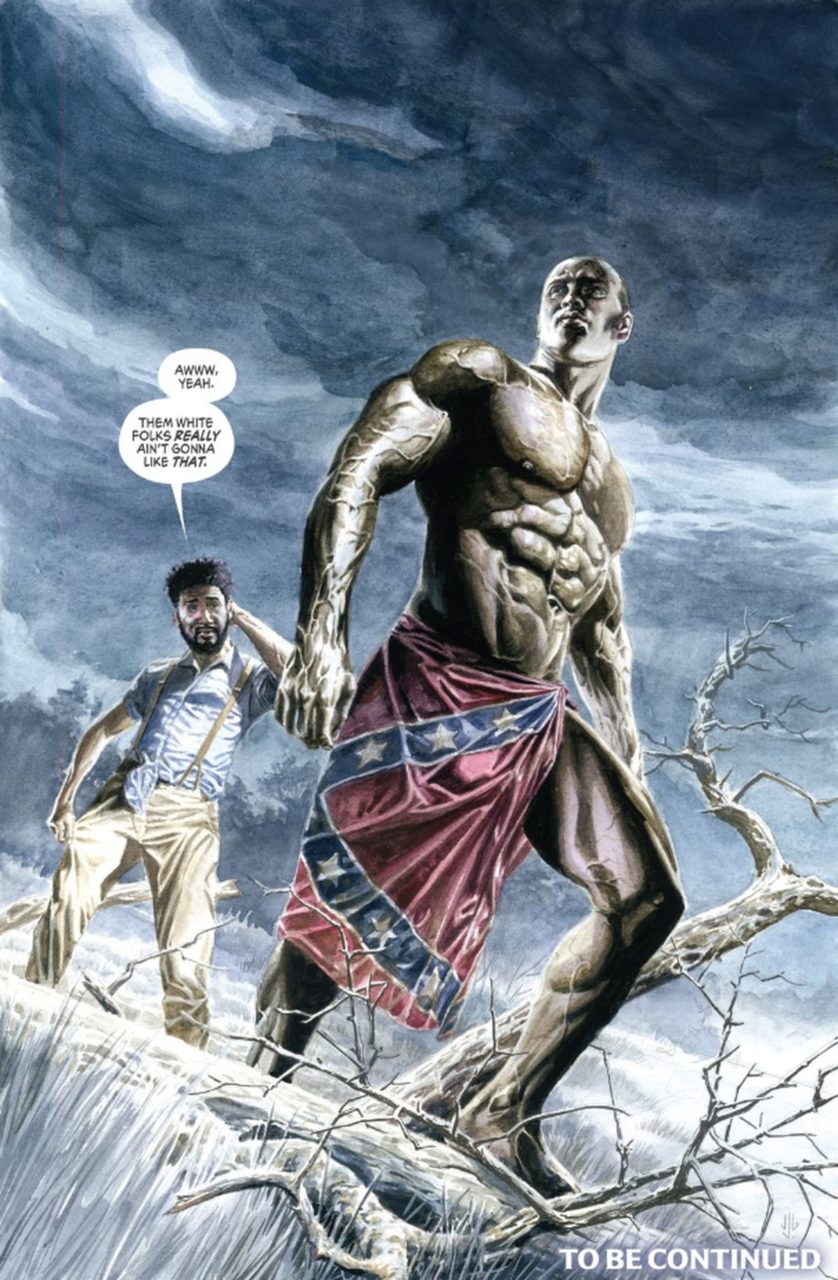

This page features the naked body of the alien — one whose physical appearance is that of a black man — holding a tree trunk, with panels done in diagonal on either side of him, with the actual alien being used as a panel border. (I’m also appreciative of the pattern at the bottom of his foot, a subtle narrative communication of him being non-human.) It’s one of the more thrilling page layouts that I’ve ever seen — but it comes with some things.

This scene is our first engagement with this alien, who, for the rest of this piece I will designate as black male, as that is how he will be read both in-universe and out of it. This black male alien is superhuman and he does not speak, or perhaps has not spoken yet but the narrative suggests that he does not or cannot. He is attacked by Klansmen who are attempting to lynch him and the other black male character whose name might be Sonny (I’m not sure as it might just be how whites are referring to him) and our alien responds with an impressive show of strength. So, our knowledge of this alien is that he’s a black man, he’s superhumanly strong, and he does not speak — and this is kind of a problem.

You see, there is a long history of stereotyping black men as being physically aggressive and displaying them as intimidating physical forces, often to the level of being superhuman. That narrative is often given in parallel with white intelligence, presenting the brutish black of preternatural strength with one hand and the smart white of great intellect with the other even when placed in exactly the same environment. Comedians Key and Peele do a great job of delineating how this coded racism has found its way into, for example, sports commentary. This depiction of the superhuman black has led to dire consequences for a number of black youth in America, to name a few: Trayvon Martin, Mike Brown, Eric Garner, and Tamir Rice. White police feel so threatened by black men, fear their purported strength, aggression, and animalistic tendencies, that they believe themselves justified when gunning them down in cold blood.

Of course, there’s the argument that, in this case, the character in question is genuinely superhuman. The alien isn’t a stereotype because it’s actually true, right? But here’s the problem: He does not speak. He does not show any capability of speaking. He has not shown any level of intelligence beyond sentience, any goals, any desires, any anything. For all intents and purposes, he could have been an animal. Sure, maybe he’s going to speak in the next issue, but I have no reason to think that he will given the way the character has been presented in this first issue. So, instead of presenting a subversion of a stereotype, the creators have managed to create the ultrastereotype by making the physicality of incredibly strong (and nameless) black man who cannot or does not speak the push of this splash page, and ultimately, his current identity.

Beyond the science fiction element, the plot is relatively by the numbers. The town is racist, we know this because white people use the word “nigger” and the Klan chases down a black man. There isn’t much about it that’s deep or nuanced, and that’s always hard to nail in a first issue, but Waid and Jones had to know that someone was going to ask them “Why you?” and “Why you on this comic?” — so I’m wondering why they didn’t answer that up front. It’s a basic set-up that didn’t evoke any resonating emotion from me at all. This might be because very few of the characters are named, or because there is (as yet) no single protagonist to relate to, but on the whole, I think it’s because I have seen almost all of these scenes before. Even the alien element does not read as either remarkable or fresh.

And then, of course, we get to where the meat is — the racial elements.

I was hardly surprised to find that for every white person who says something racist, there is always either (a) a white person to tell the other white person that they’re wrong or (b) a black person to say nothing and show no resistance. (b) happens only once, while (a) happens pretty much throughout the work. It’s a perspective common to stories of racism written by whites — in order to make white audiences comfortable, white creators (of any medium) frequently show that “not all whites” were pro-slavery or racist. It is simply inconceivable to write a story in which every white person is racist, because, in their minds, how could that possibly be true? You set the Klan up, the obvious racists, just to knock them down with white saviors, to remind readers/audiences that whites are still good people and knew better and wanted to help.

I was also similarly unsurprised to find that Strange Fruit #1 fails the Black Bechdel Test. Yes, there is more than one black person in it. However, none of them speak to each other until the very last scene. And, naturally, in that very last scene where the two black men are finally having a conversation — or where one is talking at the other — they have a conversation about white people. Because, let’s all be real for a second here, one thing is consistent about the way this comic has been marketed, titled, drawn, and written: it is all about white people. And nothing makes that clearer than the last page.

After the alien runs off the Klansmen, Sonny, the human black man, notes that white people aren’t going to like it very much if the alien runs around naked. He looks for something to cover up the alien and finds the Confederate Flag. The last page shows our superhuman black alien in a heroic pose with the Confederate Flag wrapped around his waist, as Sonny says, “Them white folks really ain’t gonna like that.”

I am dead serious. And I am furious.

Waid, Jones, and BOOM! Editorial decided that it was just fine to pose a strong. heroic black man with a Confederate Flag for clothing — as dressed by another black man.

Really.

And you want to know why? Because Waid and Jones spent a lot of time considering what white folks are or aren’t going to like without once stopping to think about what black folks really ain’t gonna like.

This is why this comic never should have been made. Not because there were missteps, not because Waid and Jones didn’t mean well, and not because white people should never write about black people at all. This comic should never have been made because there is too long a history of white people writing stories about racism and blackness, too long a history of white people shaping these tales to their own purposes, too long a history of white people writing about what they genuinely cannot understand. And above all, too long of a history of white people, particularly men, being able to do this. Not even a perfect, eleven out of ten comic would have justified the continued erasure of black voices.

If these gentlemen were so committed to telling a story about anti-black racism, then they would have brought a black writer or black artist onto the team, as Abel Meeropol did with Laura Duncan. They would have made black voices telling black stories a priority.

If these gentlemen were so committed to handling this respectfully and responsibly, then they would have decided not to co-opt a title that is clearly a part of the black struggle and is already being used by a black comics creator for a separate project that explores black history.

And if BOOM! Studios really intends on pushing comics forward, I have a number of questions about how this project continues that initiative when it is yet another example of white men writing about a marginalized people’s struggle.

So, your first question: is the comic good? Not particularly, no matter which way you look at it. The art is the best feature, but it doesn’t make up for unoriginal storytelling or any of the things I have listed above.

And your second question: should I buy it? That’s ultimately up to you, but know this: giving money to this project and contributing to its success signifies to the industry (and your peers) that you are absolutely fine with oppressors continuing to control the narrative of the oppressed. In my view, the stakes are much too high for that. For too long have white people defined what my pain is, how it should be displayed, and what stories involving it should look like. And for too long has the end result of that been the dehumanizing and devaluing of faces like mine.

Because whatever Waid or Jones would like you to think Strange Fruit means — all I see is blood on the leaves.