Content warning: You can guess, really.

The Killing Joke is considered one of the best comic stories of all time. One of the greatest Batman storylines to ever be printed. It has Joker at his worst, Gordon at his most vulnerable, and Batman at his breaking point. The book is most remembered for its graphic content, pushing the envelope at the time for mainstream comic books by fully embracing the psychotic nature of the Joker in all his sadistic corners and crevices.

Barbara Gordon is not a character in The Killing Joke. Commissioner Gordon, Batman, and the Joker are the only real characters in the story. We get insight on the Joker’s background, how his one “bad day” created the monster that he became, and how a simple turn of events twisted him inside out into the painted face laughing man. Gordon is the moral fiber of Gotham, one of the few good people left in a city that is rotting from the inside out. He has no mask, just his force of will to be good. Batman knows this. It’s why he has such high respect for Gordon, and why the Commissioner is one of Batman’s few trusted allies. They have their goodness; their moral centers that are meant to make them better, to make them heroes.

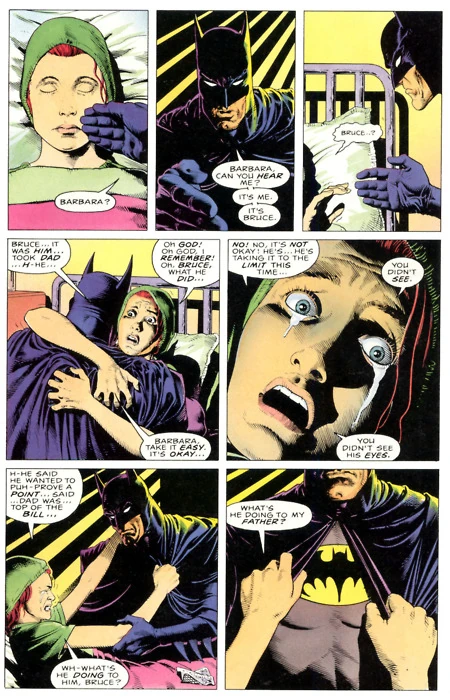

Barbara Gordon has a bullet in her stomach.

Joker’s mission in The Killing Joke is to create another Joker, essentially. To break the best of men, Batman and Gordon, by giving them a bad day, a day so terrifyingly traumatic that the goodness within them would be tainted. Their moral beliefs shattered. The Joker isn’t tempting them with an apple; he’s trying to force Gordon and Batman to eat it.

He does this by a combination of physical and emotional torture and trauma. He kidnaps Gordon, strips him of his shirt, and ties him up—the physical. But the Joker has never been a strictly physical villain. While he uses physical violence, it’s a means to an end. The true horror of the Joker is how he uses emotional violence and systematic mental torture against people. Because the Joker doesn’t have enemies. He has victims.

Barbara Gordon is his victim.

That’s all she is. Gordon is also a victim, but within the story he is not defined by his victimhood. Gordon’s opening scene in The Killing Joke is him defending inmates of Arkham Asylum and reprimanding Batman. Then he’s taken hostage, stripped naked, and forced to go on a tormented train ride where the Joker spins tales of horror and taunts him with pictures of Barbara being tortured. But in the end, Gordon is triumphant, he stands by his convictions from earlier in the book. He’s a man of the law, even in the face of a vengeful Batman and having suffered first hand by the Joker’s madness. Gordon still stands up to Batman and tells him, “I want him brought in, and I want him brought in by the book.”

Jim Gordon is meant to be the moral hero of the story. His development is key to the themes of the story itself. We, as readers, want him to be triumphant in the end, which he is. He doesn’t break, and he doesn’t give into the Joker’s taunts and prods, even when those taunts are his own daughter. Meanwhile, Barbara’s only scenes are of her getting shot and her in the hospital where she isn’t given a single line about how she feels. Rather, it’s all about her father and his feelings. Not one moment is spared to showcase her emotions or give her a sense of agency.

The Joker uses Barbara as a means to torture Gordon. That is her purpose in The Killing Joke. A tool; an object to which to be used and discarded. Her own feelings matter little, her agency and her body are stripped. Barbara exists solely to suffer. Not for her own story, but for her father’s. For the sake of creating drama, to further his storyline, and his moral dilemma. To create his “bad day.”

Barbara Gordon is shot, paralyzed, stripped naked, tortured, and photographed, and none of it is about her.

Yet despite this fact, Barbara has been consistently defined by this story. The Killing Joke eventually becoming her defining moment as a character. A story that was not about her, where she was reduced to nothing more than an object to be used in a power game between three men. Barbara suffered some of the most graphic torture seen in mainstream comics, and it has haunted her character and her fans for years.

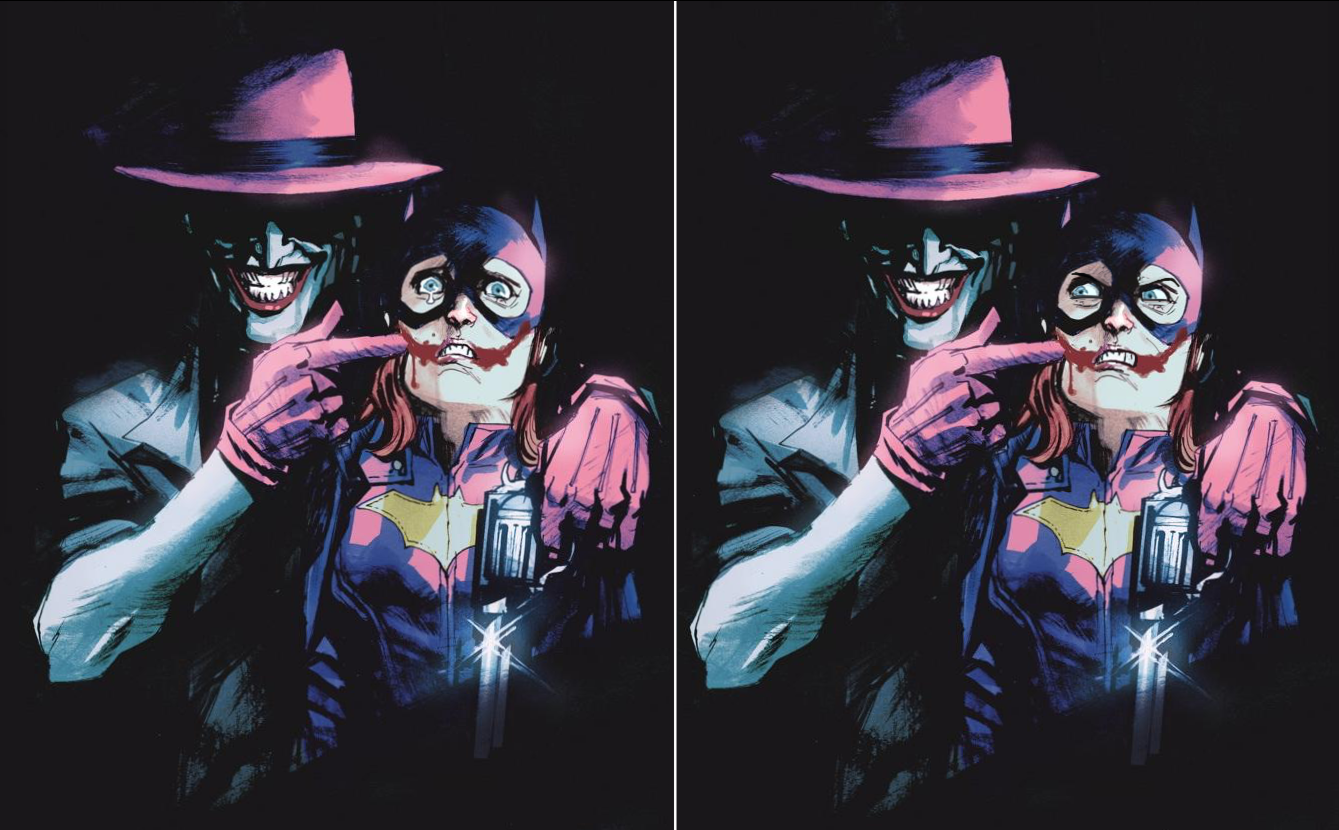

Homages such as the recently retracted Batgirl #41 variant cover call upon a certain nostalgia that The Killing Joke inspires within the comic industry. This is understandable given the story’s mass appeal and consideration as one of the best Batman comics of all time. It induces a nostalgia, which Albuquerque felt when he was commissioned to do the cover for DC Comics, a nostalgia that had some fans defending the Batgirl #41 cover. That sort of history makes it hard for artists and writers not to constantly pay homage to it and for fans not to romanticize.

The Killing Joke isn’t Barbara’s story. It’s not her origin story. It’s a documentation of her victimization.

The Killing Joke is the documentation of an iconic moment in comic history where a female character is graphically brutalized physically, mentally, and sexually for the purposes of serving the male characters stories. Barbara is shot by the Joker to kickstart Gordon’s mental torture—the start of his “bad day.” She’s then stripped naked, under goes vaguely described torture—that has a sexual tint to it—and photographed so the Joker has physical means to further torture Gordon mentally. This entire series of events is about Gordon’s story, not Barbara. As a character, Barbara holds no agency over the situation. Even her awakening in the hospital isn’t about her; it’s about her father. As a character Barbara was reduced to a plot device used to further the story of her father Gordon, a figurative object to be used against him within the narrative of the story.

The continuum of DC staff, from the editorial team, to writers, to artists, that promotes these homages of The Killing Joke starring Barbara Gordon, tend to do more harm than good. As these homages, such as the retracted Batgirl #41 cover, reduce her to this singular aspect of her history; to an object once more.

Barbara stops being Barbara and becomes the woman the Joker shot.

During this time in Barbara’s comic character history she was being showcased as Batgirl less and less, until Batgirl only appeared in special or annual titles. The character falling out of favor with current editors at DC had been relegated to making special appearances every now and again. Alan Moore, the author of The Killing Joke, then editor for DC Comics Len Wein, and former editorial director Dick Giordano, made the ultimate decision of “crippling” Barbara Gordon.

Moore has gone on record stating the following:

“I asked DC if they had any problem with me crippling Barbara Gordon—who was Batgirl at the time—and if I remember, I spoke to Len Wein, who was our editor on the project, and he said, ‘Hold on to the phone, I’m just going to walk down the hall and I’m going to ask [former DC Executive Editorial Director] Dick Giordano if it’s alright,’ and there was a brief period where I was put on hold and then, as I remember it, Len got back onto the phone and said, ‘Yeah, okay, cripple the bitch.'”

The above quote sums up the stripping of Barbara’s agency as a character in all its simplicity. It also emphasizes how these homages to The Killing Joke, particularly the focus on Barbara’s non-part in which she played, aren’t positive homages to her as a singular character with agency.

Through Barbara’s rebirth as Oracle she was able to regain her agency as a character. Kim Yale, a former writer and editor for DC Comics, grew righteously angry over Barbara’s treatment. She discussed the events of The Killing Joke with her husband, fellow writer John Ostrander.

Neither wanted the character to fall into obscurity due to her treatment in The Killing Joke. Ostrander recalled, “There were no plans for her in the continuity at that time. We decided that if that happened, we weren’t just going to make her better magically — we wanted to explore what happened when someone like her was crippled and how she would respond.”

So in 1989, Barbara made her reappearance as Oracle in Suicide Squad #38.

This was a new beginning for Barbara as she slowly began to gain recognition as Oracle, a character not defined by her disability, and a hero in her own right.

Barbara went from being a victim, to being a person who had been victimized. It may sound like semantics, but there is a key difference. Barbara struggles with depression, anger, and recovery until she finally reemerges as Oracle. An active member of the Suicide Squad, recruited by Amanda Waller herself, the main source of Batman’s information network, using her photographic member to become a technological expert, proud member and leader of the Birds of Prey, and a close friend of Black Canary, Zinda Blake, and Helena Bertinelli. Barbara took her tragedy and grew from it.

Barbara regained her agency as a character through her rebirth as Oracle.

Her journey as Oracle was all about her as a singular character. From the original mystery surrounding who Oracle was in the early Suicide Squad issues, to the final reveal that it was Barbara herself. Emerging from the ashes of her attack, and depressive state. It wasn’t about her father Gordon. It wasn’t about Batman. It wasn’t even about the Joker. Though these characters all played small parts, they’re secondary roles. They existed to enhance Barbara’s story, not overshadow it.

The Killing Joke wasn’t Barbara’s story. Oracle, and the most recent Batgirl are. There’s a reason why Cameron Stewart, one of the co-creators of the current Batgirl run, supported the cover being pulled. The story of Barbara Gordon is no longer one of a victim, a “bitch” to be crippled, but a hero. Oracle and the new Batgirl are Barbara’s stories. They belong to her, are about her, and her life. If one is going to pay homage to The Killing Joke and include Barbara in it, it should be through the lens of her story.

An artist can still make a homage to an iconic story that holds great meaning to them; even if that story is The Killing Joke involving Barbara Gordon and The Joker; however, it should be through Barbara’s own eyes. How she felt. How she feels now. A reflection of where she is currently, of who Barbara has become. No longer a victim, but a hero in her own right. A simple tweaking it really all it takes.

Ultimately, Barbara Gordon’s story should, and has been, one we as readers can root for. A story of triumph, not a story of fear. A story that dismantles the years of history that have been built up behind Barbara as a singular character, both as Oracle and her return as Batgirl. A story purposefully crafted by Yale, a woman who saw how Barbara was treated in The Killing Joke and wanted to correct it.

Where once Barbara existed as an extension of Batman and her father—as evidenced most profusely in The Killing Joke—Oracle and the new Batgirl are all about her. They are stories about her recovery, her strength, and her journey as a hero.

Given the history of female characters in comics being used as a means to further a male characters stories—whether through being killed, tortured, raped, or otherwise—any homages made to The Killing Joke using Barbara are always going to be tainted unless they are from her specific point of view. Barbara Gordon as both Batgirl and Oracle is a character that means a great deal to many people. Barbara Gordon as a character represents a story of a woman who was used by a man to torture other men in her life, who was victimized for no other reason than to be a victim, and then took her own story in her hands to become a hero. Barbara’s entire narrative is about her climbing out of the shadow of The Killing Joke. Homages such as the Batgirl #41 variant cover—a cover DC requested to be “creepier” than Albuquerque’s original piece—throw her back into that shadow. It reduces Barbara’s narrative triumph, one many real life fans can relate to, to her singular moment of ultimate victimization and reduction as a character into that of an object.

The woman cowering under the white gloved hands of the Joker, face twisted in fear and smeared with blood isn’t Barbara Gordon, the superhero. The woman with eyes wide with fear, crying as her narrative predator, the man DC won’t let her escape, holds her in a close embrace with a gun pointed down, isn’t being presented as a hero. She is being presented as the woman the Joker shot.