The Wicked + The Divine is a pretty cool comic, guys. You know this, I know this—hell, I’m pretty sure Jamie McKelvie, Kieron Gillen, and Matt Wilson know this. Lots of people have lots of different readings of it and Gillen has been kind enough to provide Writer’s Notes about his work. Still, I thought I’d share with you what I’ve found to be a pretty interesting lens through which to read the text. And, guess what? The lens even has a specific name! But I’m not going to tell you what it is just yet.

We’ll save that for the end.

For now, I’m just going to draw your attention to a couple of patterns we’ve seen in recent culture—starting with the mix of the high and low. For centuries, there was a bright line between, for example, the “high” art that is to be seen in a museum gallery and the “low” art of graffiti on a city wall. However, in more recent times, that bright line has been eroded. In 2008, a mobile home featuring work by Banksy sold for half a million pounds. In late 2013, Beyoncé took an extensive sample of critically-acclaimed novelist and short story writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche’s 2012 TEDx talk on feminism. In this day and age, mixture and melding of the high and low is not only common, it’s almost expected—and so, to a certain extent, it’s not a huge surprise that this kind of blend features so heavily in The Wicked + The Divine. On a superficial level, how this mixture of high and low culture features in the comic is fairly obvious. The very premise of the comic uses pop stars, bastions of low culture as they are, to make commentary on some very high culture topics, including the nature of religion, celebrity, and death.

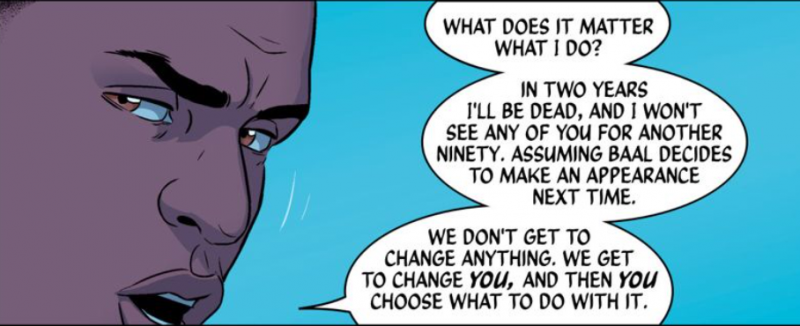

One of the clearest examples of this kind of commentary comes in issue #4 when Baal explains the Pantheon’s raison d’etre to Laura and Cassandra: “We don’t get to change anything,” he says. “We get to change you, and then you choose what to do with it.”

This explanation functions on several levels. First, in terms of plot, we can read this as an explanation of the Pantheon conceit. Baal and the other gods will die in two years or less, leaving the world in the hands of others. Next, taken in the context of pop music, it can be argued that Baal is commenting on the cyclical nature of celebrity and popular music in general—things that are en vogue one day can be gone and replaced the very next. What is meaningful is the effect their work on the world and their listeners, rather than the gods’ lives as individuals. On yet another level, this can be read as a commentary on the nature of religion itself. Most major religions are based on historical texts written several thousand years ago that have gone (relatively) unchanged across time. Instead, believers are meant to be changed by these texts and ultimately choose what to do with those changes in their lives.

Pretty clever that they pull all that out with a single line, right?

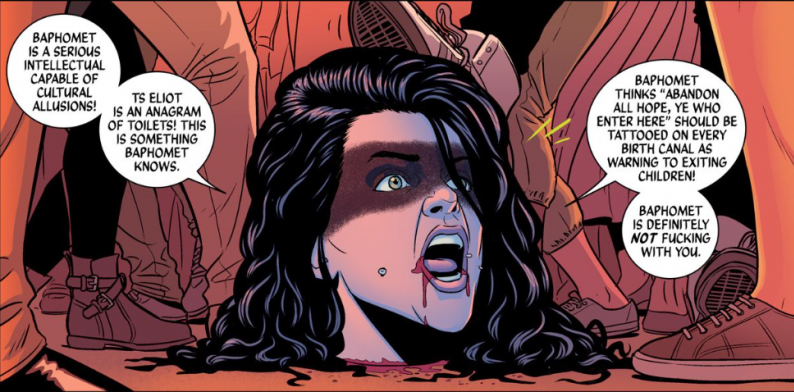

And there are still many high-low mixtures that occur purely in passing. In the third issue, the reader encounters the legendary Baphomet. There is none more goth than he. Baphomet creates the illusion of a severed head that declares, among other things, that “T.S. Eliot is an anagram for toilets” (an amazing insight that I can’t unsee) and suggests that “‘Abandon Hope All Ye Who Enter Here’ should be tattooed on every birth canal as warning to exiting children,” referring to the inscription above the gates of Hell in Dante’s Inferno. Shortly after, Laura uses a nearby skull to mimic Hamlet’s famed “alas, poor Yorick” scene in hopes of defusing a heated argument between Baphomet and another god.

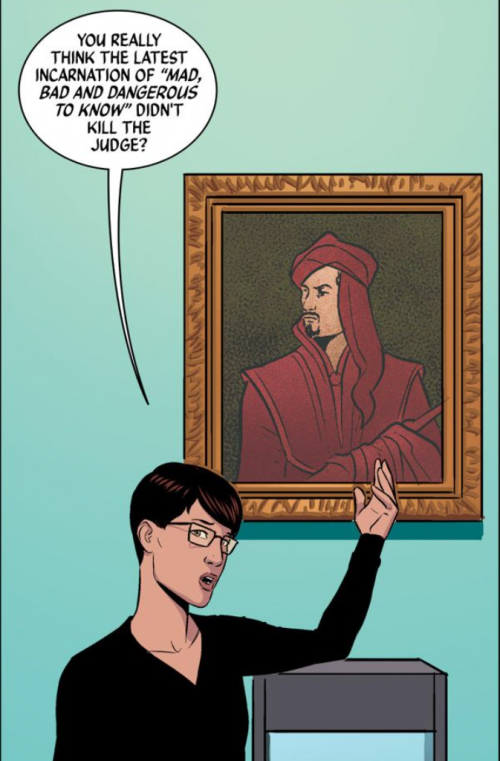

Similarly, while there are a great many pop culture references to The Beatles, David Bowie, The Daily Mail, and Facebook, there are also quite a few high culture references. In issue #2, Cassandra and Laura meet in the National Portrait Gallery and are shown in front of three portraits, discussing who may have framed Lucifer, a god of Christian mythology, for murder. During this scene, Cassandra gestures to one particular portrait while describing Lucifer as “Mad, Bad, and Dangerous to Know,” a phrase historically known to describe Lord Byron. Kieron Gillen further reveals in his Writer’s Notes that the portrait is indeed of Lord Byron and is accompanied by the portraits of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley and Percy Shelley. He even implies that these three were part of the Pantheon of their time. Thus, the low culture pop stars of 2014 belong to the very same tradition as three high culture writers of the 1800s.

Similarly, while there are a great many pop culture references to The Beatles, David Bowie, The Daily Mail, and Facebook, there are also quite a few high culture references. In issue #2, Cassandra and Laura meet in the National Portrait Gallery and are shown in front of three portraits, discussing who may have framed Lucifer, a god of Christian mythology, for murder. During this scene, Cassandra gestures to one particular portrait while describing Lucifer as “Mad, Bad, and Dangerous to Know,” a phrase historically known to describe Lord Byron. Kieron Gillen further reveals in his Writer’s Notes that the portrait is indeed of Lord Byron and is accompanied by the portraits of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley and Percy Shelley. He even implies that these three were part of the Pantheon of their time. Thus, the low culture pop stars of 2014 belong to the very same tradition as three high culture writers of the 1800s.

With that particular thought–the thought of the pop stars and literary heroes as part of the same spirit–let’s really look into this choice to make pop stars gods and what it implies.

As mentioned previously, in modern times as earlier, popular and mass culture have been viewed as the polar opposites of the high culture fields like philosophy, art, and indeed, religion. But when you collapse the hierarchy between high and low culture, you’re not just raising up low culture—you’re actually placing them in a state of equivalence where none is valued more highly than the other. WicDiv’s presentation of these musicians as goddesses and gods places pop and religion in a state of equivalence that is a statement on the importance of pop music and artists in the real world. Pop stars and their associated fans have been compared and made equivalent to religion before, though typically by evoking the more negative aspects of religion, such as the development of cults or the danger of obsession. A little more than year ago, Jack Gleeson of Game of Thrones fame shared his feelings on “celebrity worship,” a term which has become part of a psychological syndrome. However, WicDiv writer Gillen is also careful to assert that the creative team’s cultural statement is a celebration of this hierarchical compression. As he pointed out when Image announced the series early last year: “We’ve all had pop-stars save our life.”

Then, we can read the entire The Wicked + The Divine series as a critical legitimization—or, depending on who you’re talking to, affirmation—of pop music, of fandom, of youth culture. There is no cultural hierarchy because it is all equally valuable and worthy of praise, interest, and study. The same way we revere the classic, so should we revere the contemporary; as we disdain the contemporary, so should we disdain the classical. This mixture of pop music with religious figures is powerful and almost certainly intentional.

And now, children, I think you’re ready for me to tell you about the lens we’ve been using to look at WicDiv and what it’s part of. The particular technique we’ve been examining, the flattening of high and low cultural hierarchy, is known in literary theory as “pastiche” and it’s a method of postmodern critique.

See why I didn’t throw that in at the beginning? About 10% of you would have read this article if I had opened with the word postmodernism, but I think literary theory and technique can be incredibly fun and interesting when terminology doesn’t act as a gatekeeper. You were reading postmodern critique this whole time and had no idea! So, if you haven’t rage quit at my deception, let’s backtrack a little and talk about postmodernism and pastiche itself.

Postmodernism is a cultural movement from the late-20th century that was formed in response to, surprise surprise, modernism. As a term, it’s kind of confusing, since we always consider the present to be “modern times” but postmodernism is specifically responding to a period after what is considered to be the modern, which lasted from the late 19th to early 20th centuries. Really, this is a clear lesson in why you should never name anything “modern,” because there will always be something to follow it. And if you really want to get technical, we’re now in a period that’s called the metamodern, or even post-postmodern. Awful, I know.

Anyway, there are a lot of bits and pieces of postmodernism and that’s kind of the point. What the movement is really about is decentering and deconstructing. It’s hard to define because, as it is often said, postmodernism resists definition and seems to enjoy being wholly ungraspable. Annoying as that may be for someone who has to study it, it’s even more annoying for the layperson—but it’s my hope that we can make this a little more accessible.

One resource that has been helpful for me is Andrew Bennet and Nicholas Royle’s An Introduction to Literature, Criticism, and Theory. Within it, they don’t really bother trying to lay down a definition of postmodernism; instead, they give you some helpful concepts that describe most of the elements. One of these concepts, the one we’ve been talking about but never actually addressed directly, is pastiche. Bennet and Royle describe this as a “hybridization, a radical intertextuality, mixing forms, genres, conventions, media, [that] dissolves boundaries between high and low art, between the serious and the ludic.” That’s a somewhat heavy definition, so I’ll pull back from WicDiv for a second a show you what I mean with these two images (left, and below right)

One resource that has been helpful for me is Andrew Bennet and Nicholas Royle’s An Introduction to Literature, Criticism, and Theory. Within it, they don’t really bother trying to lay down a definition of postmodernism; instead, they give you some helpful concepts that describe most of the elements. One of these concepts, the one we’ve been talking about but never actually addressed directly, is pastiche. Bennet and Royle describe this as a “hybridization, a radical intertextuality, mixing forms, genres, conventions, media, [that] dissolves boundaries between high and low art, between the serious and the ludic.” That’s a somewhat heavy definition, so I’ll pull back from WicDiv for a second a show you what I mean with these two images (left, and below right)

On the left, we have an image of Mona Lisa—high art—melded with Lynda Carter’s depiction of Wonder Woman—low art. On the right, similarly, we have a recreation of Salvador Dali’s The Persistence of Memory—high art—using images/characters/themes from The Simpsons—low art. Both of these pastiches have completely collapsed the idea of what is high and what is low by smashing them together in one image. The function of this mixture is to dissolve the cultural hierarchy and make everything equally valuable. The Mona Lisa is just as important as Wonder Woman. The Simpsons are have the same cultural worth as surrealist art.

On the left, we have an image of Mona Lisa—high art—melded with Lynda Carter’s depiction of Wonder Woman—low art. On the right, similarly, we have a recreation of Salvador Dali’s The Persistence of Memory—high art—using images/characters/themes from The Simpsons—low art. Both of these pastiches have completely collapsed the idea of what is high and what is low by smashing them together in one image. The function of this mixture is to dissolve the cultural hierarchy and make everything equally valuable. The Mona Lisa is just as important as Wonder Woman. The Simpsons are have the same cultural worth as surrealist art.

And of course, the question remains: so what if it’s postmodern? What do I care? I would say that the postmodernist nature of this book–or really any book–doesn’t change all that much about the contents, but it does provide a new way of looking at a piece of cultural phenomena and the work that it’s doing. I think we could have arrived at these conclusions without the postmodernist framework, but it’s pretty cool to see that a comic fits into an overarching cultural pattern that academics have otherwise owned for quite some time.

And, actually, we can see the postmodern in this very discussion. It is only in the last decade that the comic book and graphic novel have broken out of the geek and nerd subcultures and into the mainstream. Four of the top ten highest-grossing films of 2014—Guardians of the Galaxy, X-Men: Days of Future Past, Captain America: The Winter Soldier, and The Amazing Spider-Man 2—were based on comic books.

However, this shift from subculture to mainstream pop has not yet been enough to push most commercial comics into the territory of high culture. Though comics are slowly moving into academia as institutions—the University of Oregon now offers a degree in Comics and Cartoon Studies and the University of Dundee, a Master’s in Literature/Postgraduate Diploma in comics studies—it has been said that the field is about fifty years behind film studies when it comes to academic legitimacy. Despite the growing comic phenomenon, it is widely considered to be a medium limited to stories about superheroes and stories of minimal societal value at that, especially when compared to other narrative forms. As such, WicDiv’s postmodern assertions about the nature of pop music, its relevance to society, and its role as compared to religion erase the notion of comics as low culture entirely by addressing and engaging with high culture topics directly. The Wicked + The Divine, just by virtue of existing, is an embodiment of the postmodern pastiche itself.

Very nicely done. I ookies forward to more of your observations.

Question: Was Lord Byron, Mary Shelley and Percy Shelley considered high art during their time? It’s interesting that low art shifts into high art when enough time passes like the work of Charles Dickens. I love this piece. We have many great pieces on the site but I think I’m starting to get all fangirl on you, Micheline!

Thanks for your kind words <3333

And it's interesting you should bring that up, actually. It's said that Lord Byron was actually the first "celebrity" (http://www.sunypress.edu/p-4773-byromania-and-the-birth-of-cele.aspx) which makes choosing him as a representative even more poignant–and likely intentional. Mary Shelley had a reputation for writing but didn't really get cred until after her death and instead was remembered as Percy Bysshe Shelley's husband. Percy Bysshe Shelley also didn't have much renown until after his death.

Which is so depressing as a wanna-be published/semi-famous writer, you know?

But, as a question about whether it matters–I really don't think so. That we consider them high art now is enough to make their crossing into the territory of pop stars and comics postmodern, even if that wouldn't have been so at the time.