Gorgeous, right? This is Judith and the Head of Holofernes, or Judith I, by Klimt. Gustav Klimt is enduringly famous, as his work should be — it’s also often referenced.

Gorgeous, right? This is Judith and the Head of Holofernes, or Judith I, by Klimt. Gustav Klimt is enduringly famous, as his work should be — it’s also often referenced.

Judith, the subject of the picture, is an Old Testament heroine who achieves political grace by gratifying and then beheading the general who is ransacking her land and people. His name is Holofernes, and that’s him (part of him) in the bottom-right hand corner of the painting. After that, a lot of people want to get to know her better — but she’s like, “Thanks, no.”

Klimt’s vision of Judith is overtly eroticised, called “orgasmic” by some, and illustrates the flush of physical power Judith has accessed. The brush strokes make the painting more beautiful when seen in close detail than from afar. They give the impression of a body in flux, beaming up, or of goosebumps as experienced from the inside.

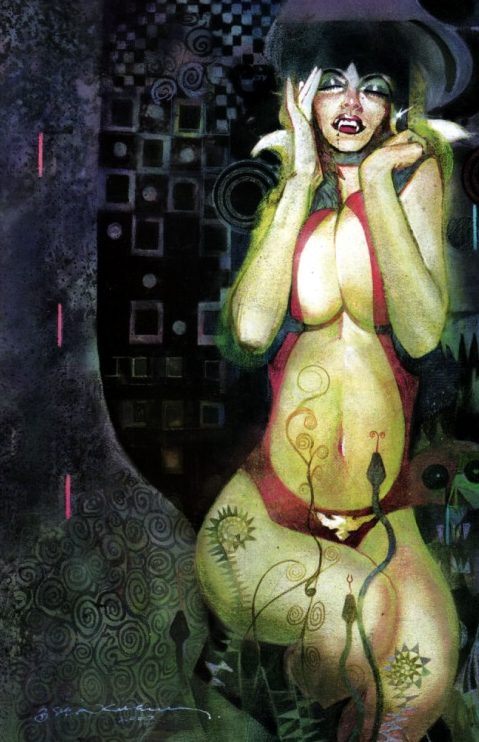

One of the references to this Klimt work can be seen below. This is a Bill Sienkiewicz piece, a Vampirella pinup. It’s a reference that works, instead of just existing, because it creates a visual joke: Vampires + beheading.

In her earlier years, Vampirella’s race consisted of not your average vampires. They’re alien vampires, for one thing, from the planet Drakulon (psychedelic excellent) where blood runs in rivers. Actual rivers, in the landscape. As Wikipedia tells it, they are “not prone to the race’s traditional weaknesses, such as daylight, holy water, garlic, or crosses.” Beheading, the final vampiric defeat is not mentioned. (Beheading is emphasised in Hammer’s The Vampire Lovers film adapted from Le Fanu’s Carmilla — an unusually woman-centric example from Hammer’s vampire canon, released one year after Vampirella’s debut. In the same month, in fact, as her graduation from comic story hostess to comic story protagonist.) Is beheading the only thing that can dispatch Vampirella, as it was for Holofernes? Or is she having the last laugh knowing even that can’t keep her down?

I’m not too familiar with her history, so I don’t know. But either way: I’m laughing. And laughter makes the heart grow fonder.

Unlike Judith, Vampirella appears alone. She is Judith and Holofernes both. The placement of her hand is different; Judith holds the head firmly with her hand, whereas Vampirella’s little finger is lifted, mocking the thought of death. Her other hand falls back, ooh la la, mercy me. Shades of The Kiss. Sienkiewicz shades a square around her face, saying yes: this is the joke. The head. The head in a box.

Unlike Judith, Vampirella appears alone. She is Judith and Holofernes both. The placement of her hand is different; Judith holds the head firmly with her hand, whereas Vampirella’s little finger is lifted, mocking the thought of death. Her other hand falls back, ooh la la, mercy me. Shades of The Kiss. Sienkiewicz shades a square around her face, saying yes: this is the joke. The head. The head in a box.

Maybe you say, “she’s not alone, I see a skull right there.” OK. What’s less present than a skull? What’s more anonymous? The skull in the position of Holofernes in the Sienkiewicz piece is not painted as completely as Vampirella is. It’s created from decorative shapes like the background; it’s in the same dark tones as the bulk of the background. The dark shades of Klimt’s Holofernes contrasts with the bulk of the Klimt piece. He’s a black hole, appropriate to his narrative, but he retains his flesh, his face, his hair, and his personhood — it’s necessary that he remain a named, nameable presence because without his history, his continuity, the picture loses its whole story. Where is the appropriate place for a skull in the iconography of Vampirella? What’s a skull to a vampire? The skull fades into the background, laughing, as skulls do, because the skull is a part of the joke.

Judith stands triumphant in her picture because she’s beaten her oppressor. Who oppresses Vampirella? Who vamps the Vampi? She does not have to worry about the battle of seducing a villain to death. That is old hat. That’s not the tension in her story.

Both women’s faces are sensual, eyelids shining and brows arced high. Judith looks at us, connecting. She did what she did for her country, her community. Vampirella is an alien who fights evil and saves us, but she’s above us on the food chain, and beyond us.

Or, second origin: Vampirella is a daughter of Lilith — another woman from Jewish lore. Whatever you get from this picture, whichever origin you prefer, this is how to do a reference! You can stick any character in any masterpiece pose; you can piggyback on anyone’s established motifs. But is there something to the connection between art and art, character and character, even artist and artist, to make the viewer remember something more than “I saw a nice picture once?” Make your artistic choices — and that includes your references — communicative.

Eye candy can be food for thought.