This is part two of my retrospective/nostalgia journey through my time as a graduate student teaching comics in the “early days.” Part one, my love letter to Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics can be found here.

At the time that I was teaching introductory composition, the Big Thing in my field was (and still is today in the more progressive first-year writing programs) was the inclusion of multimedia or visual texts, and my colleagues approached this in a variety of ways. Some employed advertisements, magazines, or other print genres, while others focused on maps, photography, or fine arts. I went the comics route, as I had just gotten into comics and they were new and exciting to me. In the grand tradition of university instructors before me, I had decided that if I had a choice, I would rather read fifty essays about something that delights me personally than ever read another annotated bibliography.

I also liked that the assignments you could do with comics were not altogether different from assignments you would do (that students might have already done) with novels and short stories. Comics is a medium, but it spans a multiplicity of genres for a variety of audiences. I favored assignments that emphasized the unique medium of comics, but also contextualized them as stories not wholly dissimilar from literary genres.

A standard assignment for our writing program was the rhetorical analysis. It’s one of those assignments that you find in an American composition course—English 101—as opposed to an intro to literature course. The main difference between the two courses is that while in both classes students may read and write essays about literature, they are more likely to discuss the themes of the texts in a literature course, whereas in a composition course, the focus is on the ways in which the author communicates those themes. For my class, the rhetorical analysis was on one of the comics from the list of comics we read throughout the semester. It was intended to be a culminating assignment, premised on their understanding of Scott McCloud, wherein they would describe a particular aspect of the comic and use visual and textual evidence to support their claim. Three of those comics were Spider-Man titles that I used as a jumping off point to a discussion of topics familiar to those interested in cultural studies—issues of genre, culture, and audience.

At the time that I taught this assignment (nearly ten years ago now) Spider-Man 2, starring Tobey Maguire and Kirsten Dunst, had just been released, so there was a general awareness that Spider-Man was a thing, even if the students hadn’t seen the films. Marvel had also just launched Spider-Man: India, a four-issue mini-series speculating how Peter Parker’s origin story could be told if Peter lived in Mumbai rather than New York.

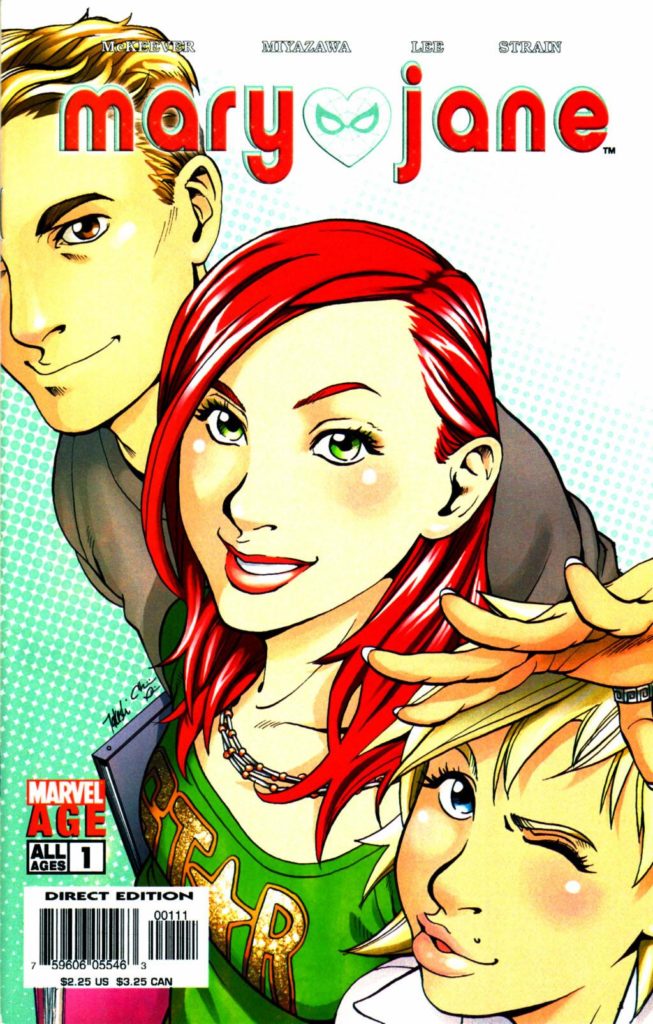

Around the same time, Marvel released the four-issue mini-series Mary Jane, a contemporary reimagining of Spider-Man from Mary Jane’s point of view. (Unlike Spider-Man: India, which was a one time miniseries, Mary Jane was followed up by Mary Jane: Homecoming and two runs of Spider-Man Loves Mary Jane, before finally being abandoned in 2009.)

As the base for our comparisons, I chose the first issue of Ultimate Spider-Man, which was, although technically a contemporary reimagining like Spider-Man: India and Mary Jane, still, essentially, Peter Parker’s story told in a traditional comic book art style, in a traditional comic book fashion, to a traditional (read: young adult male) comic book audience. The three comics complemented each other well, but they were diverse enough in terms of genre, audience, and artistic style that when we utilized Scott McCloud we were able to have lengthy and full discussions on a variety of cultural and artistic topics.

As this side-by-side comparison shows, there are a plethora of things to discuss in regards to art style, panel layout, and color alone, but we also focused on how the stories themselves compared. We looked at who “Peter Parker” was in each of the series and analyzed the changes that had been made and speculated why they had been made. We described how the story changed based on the intended audience, questioned if the changes were successful in inviting in a specific audience, and discussed how it made them feel when they were not the intended audience. All in all, I considered it to be a successful assignment.

Three things stand out in my memory.

- Against probability, I had at least one male South Asian student in each class.

- My male students absolutely hated Mary Jane and resented even having to read it. (Honestly, I’m not sure all of them did.)

- My female students, on the whole, said that they enjoyed Mary Jane and thanked me for even assigning it (although not in front of their male peers).

It was that vocal and not-at-all-unforeseen split between male and female students that ultimately made the assignment worthwhile for me. Comics offer a selection that is beyond diverse, and the industry as a whole has made great strides in publishing more comics by women and about women. This was the first time I’d seen a comic published by one of the “Big Two” about a woman who wasn’t a superhero, who wasn’t intended to be a love interest (in fact, you can argue that Spider-Man is her love interest), in a comic whose main audience was not actually male. It was an experiment, to be sure, but it was one that resonated with me at the time. It still resonates today, and the conversation about what it means to create comics for a female audience—or even to just admit that they exist—is more important than ever.

I taught composition using comics for close to five years, and this was just one assignment of many that I created. I am happy to share the syllabi, assignments, and handouts I created with interested colleagues, and would love to hear about other assignments that people have done or are doing currently. I also want to thank the lovely editors at WWAC for allowing a recovering academic to reminisce and share her experiences.

Find Katherine on twitter or contact her by email!