Just before Julius Caesar informs Brutus that “the fault . . . is not in our stars,” he makes a more startling observation: “Men at some time are masters of their fates.” The qualification, “at some time,” is key to understanding The Fault in Our Stars, a film already powered by a devoted fanbase to top box office earnings. It asks us to consider if we are capable of controlling our fates, of being remembered despite our short time on this earth, and if that is really what we want to achieve.

Just before Julius Caesar informs Brutus that “the fault . . . is not in our stars,” he makes a more startling observation: “Men at some time are masters of their fates.” The qualification, “at some time,” is key to understanding The Fault in Our Stars, a film already powered by a devoted fanbase to top box office earnings. It asks us to consider if we are capable of controlling our fates, of being remembered despite our short time on this earth, and if that is really what we want to achieve.

Viewers unfamiliar with Nerdfighteria or the Vlogbrothers (TFIOS author John and entrepreneur/biochemist Hank Green) may not be aware that The Fault in Our Stars was inspired by (but not based on) the story of Esther Earl, a young vlogger and Harry Potter fan. The sixteen-year-old was diagnosed with metastasized papillary thyroid cancer in 2006 and continued to participate in the fandoms she loved, even helping to raise $250,000 for the Harry Potter Alliance. Green dedicates the novel to her, but makes it clear that Hazel Grace Lancaster is not Esther. The two girls share similarities but developed different approaches to their lives, and one is not better than the other.

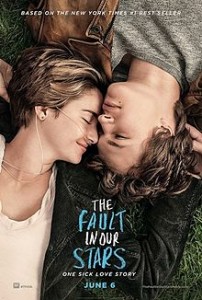

Hazel Grace, played by Shailene Woodley, has curled into herself after three years of living with thyroid cancer. She seems resigned to what she’s been given, a stark girl looking at a stark world without surprise at the bad lot assigned to her. Woodley improves with each film, and her portrayal of Hazel is enriched by the tiniest movements and looks. She’s hard to read at the start of the film, a girl very clearly distanced from people except for her parents, and understandably so. Forming close relationships can be a hazard when you’re “a grenade,” as Hazel declares angrily at one point. “I’m going to obliterate everything in my wake.”

Augustus Waters decides to stick around anyway.

He’s turned out to be a polarizing character in the 18 or so months since the release of the novel, and reactions tend to run the gamut between odes to his perfection and complete distaste for his metaphors and general pretentiousness. Ansel Elgort plays up the flirty smiles and ostentatious words charming Hazel Grace despite herself, but his first introduction on screen says most of what the rest of the film will reveal about him: Gus is afraid. He doesn’t fear death, but the inability to do something meaningful, to be remembered. And so he affects confidence, an easy smile and laugh, sticking a cigarette into his mouth and holding on to the idea that he isn’t giving “it the power to do its killing.”

He’s turned out to be a polarizing character in the 18 or so months since the release of the novel, and reactions tend to run the gamut between odes to his perfection and complete distaste for his metaphors and general pretentiousness. Ansel Elgort plays up the flirty smiles and ostentatious words charming Hazel Grace despite herself, but his first introduction on screen says most of what the rest of the film will reveal about him: Gus is afraid. He doesn’t fear death, but the inability to do something meaningful, to be remembered. And so he affects confidence, an easy smile and laugh, sticking a cigarette into his mouth and holding on to the idea that he isn’t giving “it the power to do its killing.”

The population of this film is quite small, with Laura Dern and Sam Trammell as Hazel’s parents and a smirking Nat Wolf as Isaac, Gus’s best friend, leaving most of the map for Hazel and Gus to inhabit. Woodley and Elgort don’t have instant chemistry, but as the film goes on, they seem to orbit one another. Director Josh Boone shoots close-up after close-up of the pair, pressing intimacy upon the audience to varying levels of success—I was most charmed by the first few glances that Hazel and Gus exchange in “the literal Heart of Jesus,” the church setting for their cancer support group. There are small concessions to the physical challenges that both characters face as Gus stretches out his prosthetic leg after sitting on a picnic blanket, and Hazel juggles two cartons of eggs with her oxygen bag slung over her shoulders. The climb up to the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam is difficult to watch, and Hazel’s determination leads to her becoming winded and weak from the flights of stairs and ladders. Boone doesn’t aim for glamorous shots, letting the characters remain the focus of the film.

Does it succeed at what it tries to accomplish? As a fan of the book, I would say so. Hazel grows beyond the distance she had tried to place between herself and the people she loves to save them pain. Gus is understandably not as perfect as he may seem, his assured attitude giving way to an honest sadness. “Pain demands to be felt,” reads Hazel’s favourite book, An Imperial Affliction, and to limit that to the love story between Hazel and Gus would do the idea a disservice.

The film gives time to the relationship between Hazel and her parents, especially her mother, who struggle with the impending loss of their only child. But stronger than the demand of pain to be felt is its demand to be shared. Gus may learn to let himself feel the pain of what his life is, but Hazel learns to let go of the guilt she carries about leaving her parents. My favourite scene in the whole film was a heated confrontation in which Hazel reveals to her parents that, at thirteen, she had heard her mother sob over not being a parent anymore. Our instinct to define ourselves by the connections we make is part of being human, and watching Hazel and her parents come to terms with what that means for them and their limited time together was simply astonishing.

And that’s the question, isn’t it: is it possible to know who we are by the time we die? Is it possible to ensure that we have lived meaningful lives and done fulfilling things before we close our eyes for the last time? The Fault in Our Stars gives a quiet assent, content to live in its own little infinity before another story comes along.